Jacquin Maud

Courtauld Institute of Art

Motherhood across the Iron Curtain: on Zofia Kulik and Mary Kelly

In Western Europe, the concept of motherhood has been at the heart of feminist claims throughout the XXth century. At first, activists extolled motherhood as the highest human achievement and as woman’s most important duty. In the 1970s feminists violently denounced this “maternalism”, refusing to acknowledge motherhood as a universal female vocation. In France, Simone de Beauvoir, for whom affirmation of the female as first and foremost a human being, involved the transcendence of the body, stated that woman’s creative potential is enslaved to “her whole organic structure that is adapted for the perpetuation of the species”. In 1981, in Mother-Love: Myth and reality, Elisabeth Badinter attacked the idea of an instinctual basis for motherhood, which she defined as a cultural construction. 1 See Ann Taylor Allen, Feminism and Motherhood in Western Europe 1890-1970, Palgrave Macmillian, 2005. A few years earlier, the American artist Mary Kelly – who lived in Britain for twenty years – had adopted the same stance in an internationally-acclaimed artwork Post-Partum Document (1973-1979) [Fig. 1]. In this conceptual piece, the artists documents and analyses her relationship with her son over a five-year period using linguistics and psychoanalysis. The work, divided into six parts, is composed of overlapping collected objects, Lacanian diagrams, charts and texts, and offers no visual representation of the mother or the child.

Fig. 1 – Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, 1973-1979. Installation view at Anna Leonowens Gallery, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, Nova Scotia

In Eastern Europe, motherhood did not attract the same critique. The Communist system, which was oriented towards the future, paid attention to children, and as a consequence, mothers were granted more rights and practical assistance than in Western Europe (very long maternity leaves, wellorganised daycare centers…). Apart from those advantages, however, mothers were not shown any particular gratitude or consideration, but as they did not have to advocate for similar government concessions, there was no feminist movement. 1 See Ines Rieder, Feminism and Eastern Europe, Attic Press, Dublin, 1991. Another important difference lies in the censorship of psychoanalytic theory by the Communist system. The pre-Freudian nature of Eastern Europe societies, confirmed by Julia Kristeva who left Bulgaria for France, manifests itself notably in the total absence of introspective subjectivity. 1 “Freud… Here is somebody who was totally absent form my conceptual field – my Eastern culture was Russian and German (it included German philosophy, Kant, Hegel…) but absolutely not Freudian. I discovered Freud in France through Tel quel and then through Lacan” in Julia Kristeva, Au Risque de la Pensée, Editions de l’Aube, Paris, p. 112, 2001. In this undeniably different context, at the same time as Kelly’s Document, the Polish artist Zofia Kulik and her artist partner Przemyslaw Kwiek – known as the artist couple KwieKulik – created a far more obscure work entitled Activities with Dobromierz (1972-1974) which consisted of seven hundred color slides and two hundred black-and-white photographs taken over two years, in which their son Dobromierz appears alongside various household objects. In the creative process, the respective roles of Kwiek and Kulik remain relatively indeterminate. Yet it seems that Kwiek had a dominant role and often reduced Kulik to silence. 1 See Joanna Turowicz, The Rebellion of a Neo-Avant-Garde Artist, Interview with Joanna Turowicz. Today Kulik alone presents Activities with Dobromierz, speaking for KwieKulik, and in a sense, reducing Kwiek to silence in her turn. For the purpose of this essay, I will analyse Activities with Dobromierz from Kulik’s point of view.

Post-Partum Document and Activities with Dobromierz, although created in two different societies, share striking similarities. Mary Kelly and Zofia Kulik both document and display their intimate relationship with their child. Both offer an analytical and constructed vision of their intimacy. Nevertheless, as Zdenka Badovinac explains when she compares the signification of performances in the West and in the East, “there are no essential differences (…), the difference lies in something invisible and non-signified (…), it lies in the fact that similar gesture are read differently in different spaces.” 1 Zdenka Badovinac (Ed.), The Body and the East, from the 1960s to the Present, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, p. 10, 1998. Kelly’s involvement in feminist movements and interest in psychoanalysis inform her conception of motherhood. For Kulik, whether consciously or not, being an artist in Communist Poland has not only affected her recognition but also influenced and structured her overall opus.

Mary Kelly and Zofia Kulik choose to put their intimate lives on public view. In both cases, they use their experiences as mothers as a means of transgression, asserting their commitment to social change. For both artists, the personal is the political. However, this statement, well-known in the West as a feminist slogan, takes on a different meaning in the East.

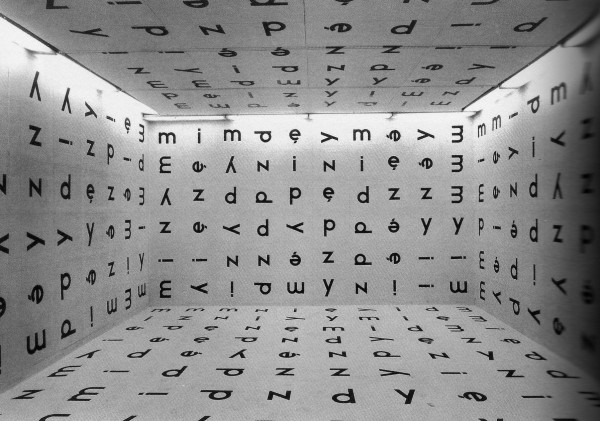

Mary Kelly’s work must be interpreted in the light of her feminist activism in the 1970s in Britain. Her involvement in feminist movements has been widely described in literature and I will confine myself to her collaboration on the film Nightcleaners (1970-73) and the documentary exhibition Women and work (1973-75) as well as her position as the chairperson of the Artist’s Union. 1 See Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Framing feminism: Art and the women’s movement. 1970-85, Pandora, London, 1987; Margaret Iversen, Douglas Crimp, Homi K. Bhabha, Mary Kelly, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, 1997; Helen Molesworth, ‘House Work and Art Work’, in October, 92, pp. 71-97, Spring, 2000. Post- Partum Document makes explicit the reality of women’s labour as mothers. The precision of the charts and the repetitive nature of the layout echo the tediousness of their tasks [Fig. 2].

Fig. 2 – Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, Documentation I, Analysed faecal stains and feeding charts, 1973-79

Kelly also reasserts the value of the female experience when she affirms that motherhood is itself a subject position. While psychoanalytic literature has traditionally emphasised the development of the child, the artist addresses the subjectivity of the mother revealing her fantasies and disentangling her from the baby’s needful view of her. 1 See Dale Mendell, Patsy Turrini, The Inner World of the Mother, Psychosocial Press, Madison CT, 2003. As Andrea Fraser stated, “The Experimentum Mentis texts do not simply reiterate psychoanalytic formulas, but they supplement them with an analysis of the mother’s experience, which doesn’t complete but rather challenges the phallocentric assumptions of psychoanalytical theory.” 1 Andrea Fraser, ‘On the Post-Partum Document’, in Post-Partum Document, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, p. 215, 1999.

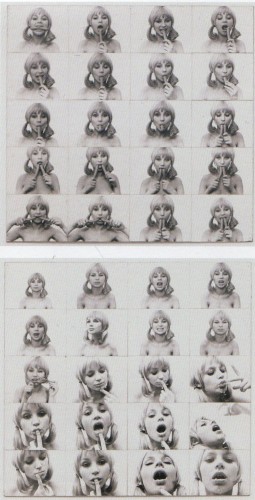

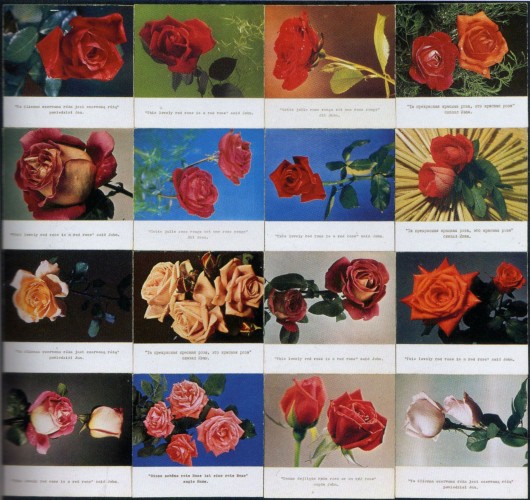

Post-Partum Document, with its profound denunciation of the withdrawal of the mother into the private, silent space of the home, makes literal fact out of the feminist assertion that the personal is the political. Kulik’s Activities with Dobromierz cannot be understood similarly. In Poland feminism was denounced as a decadent bourgeois ideology by the ruling Communist party. Women were told that they were equal to men – which was true before the law – and because of this had no need for a separate women’s movement. The only “feminist” organisation in Poland – the Women’s League – was closely affiliated with the Party and was mainly in charge of propagating socialist ideology among women. 1 See Sharon Wolchik, Alfred G. Meyer, Women, State, and Party in Eastern Europe, Duke University Press, 1985; Ines Rieder, Feminism and Eastern Europe, Attic Press, Dublin, 1991. Although in the 1970s, a few Polish artists conveyed a feminist dimension in their works – Natalia LL’s Consumer Art series [Fig. 3], which refers to erotic advertisements, Maria Pininska-Beres’s soft organic candy pink shapes and Ewa Partum’s radical pieces [Fig. 4] – their actions did not contribute to the creation of a feminist movement comparable to that of the West. 1 The work of Natalia LL was all the more shocking as there was no advertisement at all in Poland because of the frequent shortages of common goods. 1 See Le XXe Siècle dans l’Art Polonais, AICA Press, Paris, 2004.

Fig. 3 – Natalia LL, from Consumer Art series, 1972

Fig. 4 – Ewa Partum, from Self-Identification series, photomontage, 1980

In what sense, then, does Kulik’s work illustrate the dictum “the personal is the political”? Totalitarian societies impose a control on individuals which extends into their private lives. As Milan Kundera said: “in a totalitarian society, the Kafkaesque manifests itself by erasing the line between public and private life.” 1 C. Gopinathan Pillai, The Political Novels of Milan Kundera and OV.Vijayan, A Comparative Study, Prestige Books, New Delhi, p. 10, 1996. In her Activities with Dobromierz, Kulik not only deals with her own son, but also insists on the family rituals that punctuate their everyday life. For Easter, she uses the turkey and the onions they have been offered by their family to compose geometrical motifs on the floor [Fig. 5]; for the first of May the child appears in his pram holding a red flag [Fig. 6]. 1 Kulik’s and Kwiek’s fathers were both officers and as such received onions, potatoes, coal or fabric as allowance

Fig. 5 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 6 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

In so doing, she underlines the importance of private life for escaping the overwhelming power of the party and, in a way, asserts her independence. While Western feminists attack women’s domestic labour as muting and isolating, Kulik embraces the home as a resistant sphere of uncensored thought. However, her relation to private and public spheres is much more complicated. Taking advantage of the necessary daily walks with her son, Kulik brings home elements belonging to the “outside” world (red flags, cubes of ice…) [Fig. 7 – Fig. 8].

Fig. 7 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 8 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

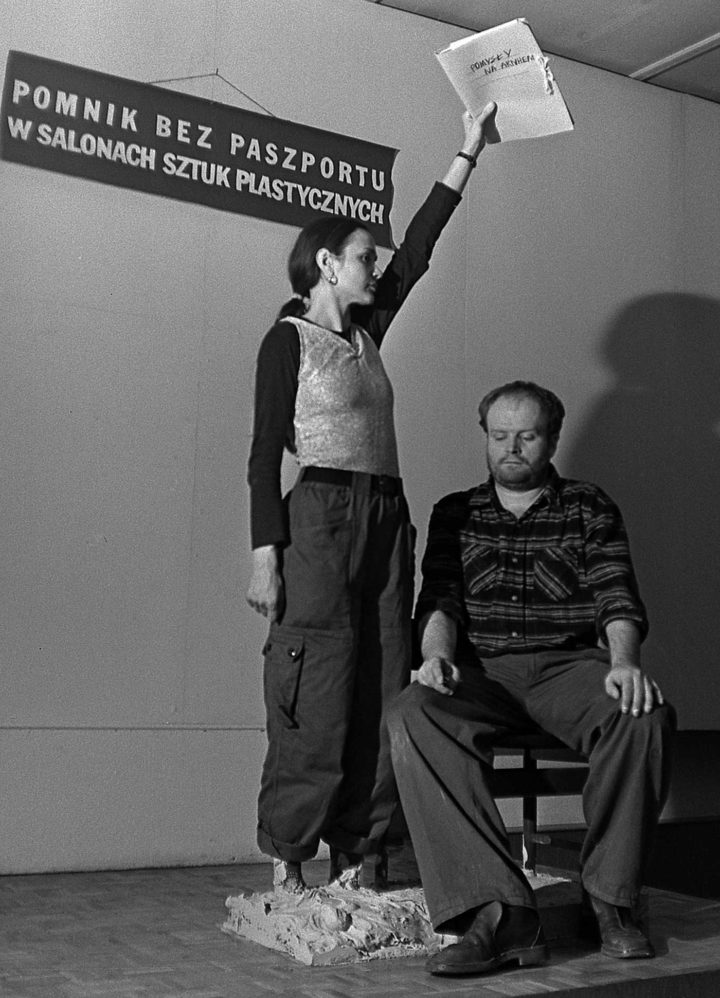

Beyond the symbolic value of these objects – for Kulik, the symbolic meaning is so internalised that it loses its relevance – the artist manifests her intention to remain within the system and to bring about a revolution from the inside. “We wrote petitions, we tried to join the communist party even if it did not work out as we were far too critical, we wanted to change the reality.” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007. Throughout the years, Kulik and Kwiek maintain this stance notably in their performances. Their contextual works constitute an acerbic critique of the totalitarian regime which they dared to oppose, sometimes to their own cost (their passports were taken away and they created Monument without a passport [Fig. 9] as an answer).

Fig. 9 – KwieKulik, Monument without a Passport in the Salons of Fine Arts, 1978

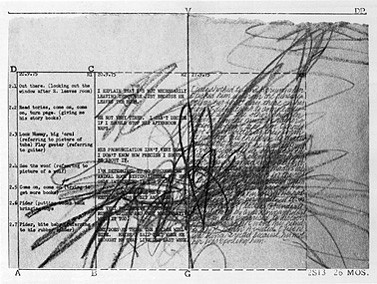

This `involvement’ radically distinguishes KwieKulik from the conceptual artists of the time – e.g Smietanka group, Jaroslaw Kozlowski or Slawomir Dróżdż… [Fig. 10 – Fig. 11] – who advocated a sharp separation from the state not to compromise themselves. Kulik echoes this split when she says “Certainly we were pathologically naive then. However, the people who made an indirect criticism of the system between the lines (…) and would, at the same time receive their remuneration from the system and reinforce the ruling stagnation were also pathological.” 1 Zofia Kulik quoted in The Rebellion of a Neo-avant-garde Artist, Interview with Joanna Turowicz, p. 5.

Fig. 10 – Jaroslaw Kozlowski, Exercise of Semiotics, 1977

Fig. 11 – Slawomir Dróżdż, In-between, 1977

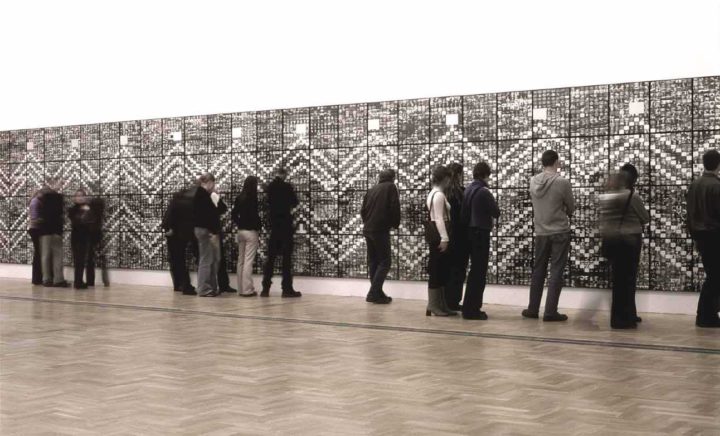

By documenting their relationships with their children over several years, both Kelly and Kulik construct a certain type of archive. It is significant that the notion of archive imbues the majority of both artists’ work. As Kelly testifies, she “[begins] (…) all [her] projects by making an archive”. For her, the collected material served “not necessarily as objective documentation, but as interrogation of [her] own preoccupation with these events.” 1 Mary Kelly quoted in Juli Carson, ‘Mea Culpa: A Conversation with Mary Kelly’, in Art Journal, 58, no. 4, p. 75, Winter, 1999. From 1984 to 1989, in order to create Interim, she collected conversation she had with women who were involved in the second wave of feminism ; in 1999, for Mea Culpa, she gathered photographs from magazines and television images related to horrors under investigation by the International War Crimes Tribunal. Besides, given the psychoanalytic dimension of Kelly’s approach, one can see in her archiving process a metaphor for the functioning of the psyche. 1 See Meredith Brown, An Activist’s Archive: Meaning and Materiality in Mary Kelly’s Post- Partum Document and Mea Culpa, MA essay, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2006. Similarly, Kulik assigns great importance to archives, which culminated in From Siberia to Cyberia (1998-2004) [Fig. 12] for which she gathered more than sixteen thousands photographs. 1 For her diploma piece, she compiled five hundred slides taken over a year. From 1971 to 1987, when she created The Studio of Activities, Documentation and Propagation (PDDiU), she documented her own performances with Kwiek as well as the works of many Polish and foreign artists; For her photomontages, she realised in-depth historical researches on decorative motifs and built up a gigantic collection of images of her model Libera in different poses, that she called The Archive of Gestures. Amassing archives is at the heart of KwieKulik “process-based art”. At the Academy, thanks to Oskar Hansen’s theory of the Open Form, Kulik “acknowledged a process as a work of art (…), and documentation as a work of art.” 1 Interview with Maryla Sitkowska, Warsaw, 1986-1995. But Kulik’s stance of “documenting and archiving anything, all symptoms of life and creation, and [her] own individual context” takes on another dimension in a totalitarian context. 1 Zofia Kulik quoted in Hans Gunter Golinski, ‘Self Portrayal as a Metaphorical Concept’, in Zofia Kulik, From Siberia to Cyberia and other works, Museum Bochum, Kunsthalle Rostock, p. 71, 2003. In the Archaeology of Knowledge, Foucault explains how the archive “shapes our relation to the past and the construction of historical meaning.” 1 Charles Merewether, The Archive Book, Whitechapel / The MIT Press, London / Cambridge MA, p. 11, 2006. Creating an archive amounts to selecting what will be remembered and what will be forgotten. And if like Derrida, we believe that “there is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory”, then Kulik’s archival mania becomes a political act. 1 Jacques Derrida, Mal d’Archive, une Impression Freudienne, Editions Galilée, Paris, p. 4, 1995. When she elaborates an archive, the artist rescues from oblivion what the state condemns. She creates a counter-memory.

Fig. 12 – Zofia Kulik, From Siberia to Cyberia, 1998-2004

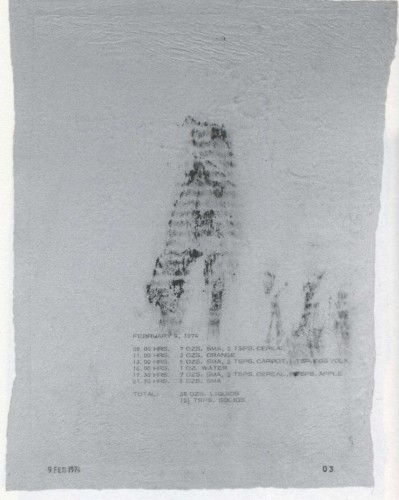

While Kelly and Kulik reveal their intimate relationship with their child, they avoid any form of sentimentality. Indeed, they do not record their daily life in a spontaneous way but rather offer a rigorously constructed vision of it. Despite the presence of emotionally-charged elements in the Document – the texture of the nappies, the scribblings and the utterances of the child [Fig. 13 – Fig. 14] – and of moving pictures in Activities with Dobromierz – some photographs remind those of a family album [Fig. 15] – Kelly and Kulik both adopt a dispassionate approach.

Fig. 13 – Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, Documentation I, Analysed Faecal Stains and Feeding Charts, 1973-79

In the Document, Kelly reduces emotion to the minimum. In so doing, she aims to challenge the traditional vision of femininity in art associated with decorativeness, sentimentality and visual pleasure. According to Griselda Pollock, the artist represents her experience as a mother by making use of traditionally masculine “tools”: the intellectual discipline and rigour which great art requires. 1 See Griselda Pollock, ‘Interventions in History’, in Mary Kelly Interim, Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, pp. 40-53, 1990. Thus, she imposes upon the viewer the conflict between the roles of woman-mother and artist. Moreover, Kelly’s work, while based on observation is filtered through the schemas of Lacanian psychoanalysis. As Lippard explains, the use of a scientific discourse is a denounciation of the generally held assumption that women’s understanding of the role of mothering is instinctive and natural. When Kelly describes motherhood as a constructed meaning rather than a biological truism, she manifests her antiessentialist stance in opposition to the first generation of Anglo-American feminists such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, who focused on the female body. 1 See Lucy Lippard, Preface, in Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, pp. xix-xxiv, 1999.

Fig. 14 – Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, Documentation III, Analysed Markings and Diary-perspective Schema, 1973-79

The deliberate avoidance of photography in Post-Partum Document also adds to the general impression of cool rationality. Once again Kelly’s strategy illustrates her feminist involvement. Indeed, in the late 1960s, a new generation of theorists were drawing on semiotics to question the inherent meaning of the image. Simultaneously, Baudrillard and Debord criticised our increasingly image-saturated culture. From those questionings, the feminist film theorists Laura Mulvey and Mary Ann Doane elaborated explicit critiques of the culture of the “gaze”. Historically, women have always been the object of the male gaze, which turns them into fetishes to palliate the anxiety of castration, and thus have been forced to identify with this masculine gaze when viewing an artwork. 1 See Laura Meyer, ‘Power and Pleasure: Feminist Art Practice and Theory in the United States and Britain’, in Amelia Jones (Ed.), A Companion to Contemporary Art since 1945, Blackwell, London, pp. 317-342, 2006; Amelia Jones, the Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, Routledge, London, 2003.

Fig. 15 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

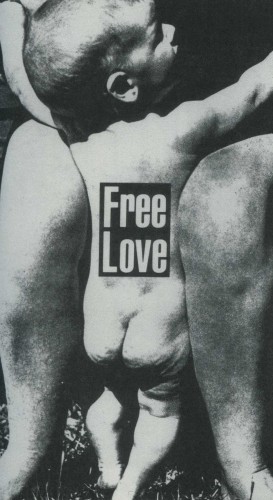

By refusing to exhibit pictures of mother or child, Kelly – distancing the spectator in a Brechtian fashion – refuses to represent women as the object of the gaze but rather to give them the position of subject. “I have problematized the image of the woman not to promote a new form of iconoclasm, but to make the spectator turn from looking to listening. I want to give a voice to the woman, to represent her as the subject of the gaze.” 1 Mary Kelly quoted in Mary Kelly Interim, Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, p. 54, 1990. At this stage, one could draw a comparison with Barbara Kruger’s Free Love [Fig. 16], in which she combines a photograph of a baby between her mother’s knees and the slogan “Free Love”.

Fig. 16 – Barbara Kruger, Free Love

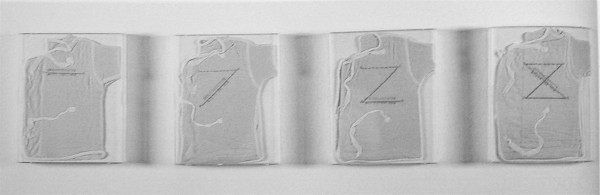

Like Kelly, Kruger calls into question essentialist assumptions about motherhood. She attacks the idea of unconditional maternal love while she defends freedom of choice. Moreover, by mixing commercial slogans with poor quality photographs, she undermines the archetype of the woman as object which reaches its paroxysm in advertising. 1 See Kate Linker, Love for Sale: The Words and Pictures of Barbara Kruger, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1990; Therese Lichtenstein, ‘Images of the Maternal: an Interview with Barbara Kruger’, in Representations of Motherhood, Yale University Press, New Haven / London, pp. 198-203, 1994. More concretely, in the Document, the overwhelming impression of detachment echoes the artist’s main concern: to document the separation between the mother and the child. She analyses the three stages of separation as described by Lacan (Weaning from the breast, from the Holophrase, from the Dyad) until the definitive acquisition of writing. The mother, frustrated by her “lack” of the phallus, substitutes the child for it. Thus, as her son progressively builds his individuality, the mother re-experiences the trauma of castration. The woman is deprived of her pleasure in the child’s body but also in her own body, which has lost its plenitude. The series Introduction [Fig. 17] perfectly illustrates the progressive separation of the child from his mother and the suffering it implies. Kelly presents her baby’s carefully folded vests, on which she has drawn progressively more components of a Lacanian diagram. At the end of the process, the last vest is “literally crossed out, denied.” 1 Margaret Iversen, ‘The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Own Desire: Reading Mary Kelly’s Post- Partum Document’, in Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, p. 209, 1999. The whole series makes visible the confrontation between the intimacy of the mother-child relationship – which the shirts refer to – and the theory embodied in the Lacanian schemas. As Lynne Tillman stresses, this theory “occupies the position of the father in the Oedipal triangle – the “term” that the mother both refers the child to and struggles against.” 1 Mary Kelly Interim, Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, p. 59, 1990. According to Margaret Iversen, the “traumatic effect of the mother’s experience is recapitulated (…) by the use of very private, vestigial signs (…) on the one hand, and an utterly abstract scientific discourse on the other.” 1 Margaret Iversen, ‘The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Own Desire: Reading Mary Kelly’s Post- Partum Document’, in Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, p. 208, 1999.

Fig. 17 – Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, Introduction, 1973-79

Fig. 17

In Kulik’s Activities with Dobromierz, one can find the same kind of articulation between intimacy and theory, and the same distant attitude. However, if Kelly’s work is informed by feminist and psychoanalytic theories, Kulik claims not to have had access to such theories. Indeed, as Sarah Wilson says “the Soviet eradication of the introspective, post-Romantic, post-Freudian subjectivity that was all Europe’s heritage before 1939 was one of Eastern block’s greatest tragedies.” 1 Sarah Wilson, ‘Discovering the Psyche: Zofia Kulik’, in From Siberia to Cyberia, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, p. 66, 1999. Then how can we explain this impression of detachment in Kulik’s work?

Hardly ever is Dobromierz represented with his parents. In most photographs he is left alone lying on the floor at the centre of strange compositions of familiar objects. Whether laughing or crying, the child looks rather confused. As Kulik explains, the detachment that she conveys is the result of the political system in which she lives and of the education she received. Indeed, as the Communist system is orientated towards the future, the individual, who becomes a mere pawn, is asked to sacrifice himself for the cause. Then, “there is no place for introspection, no place for the expression of feelings; the only things that matter are universal and social issues. You are not here for pleasure, you are here for the future, the Party, the State.” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007. Consequently, family life becomes a masquerade and its members content themselves with respecting the rituals and traditional ceremonies omnipresent in Kulik’s work. This family model perfectly matches the artist’s description of her own childhood: “[her] father was an officer (…) everything was devoted to work (…) [her] family exactly fitted the system.” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007.

As with Kelly, theory structures the whole project. From 1972 to 1976, following Polish tradition, KwieKulik attended seminars on linguistics, logic and mathematics in Warsaw. Combining their theoretical background with art, they undertook researches into visual syntax. In their work entitled Unknown Quantity X [Fig. 18], the artists build an exhaustive list of the ways one can position an object – the Unknown Quantity X – relative to the objects that surround it (under, inside, behind…).

Fig. 18 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), Unknown Quantity X, 1972-74

In so doing, they aim at creating “a certain new language in which the unknown quantities could be filled with any content for various purposes depending on a context and one’s ego.” 1 Interview with Maryla Sitkowska, Warsaw, 1986-1995. Actually, Activities with Dobromierz is a direct application of this model, in which the child has been substituted for the Unknown Quantity X [Fig. 19 – Fig. 20].

Fig. 19 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), Unknown Quantity X, Under, 1972-74

Fig. 20 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

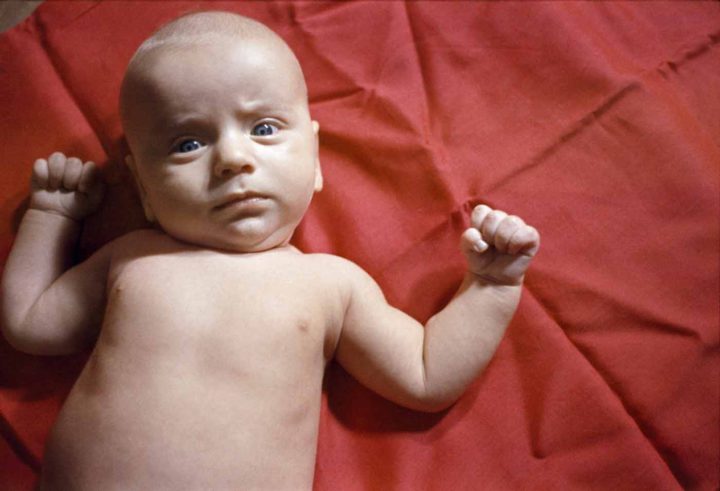

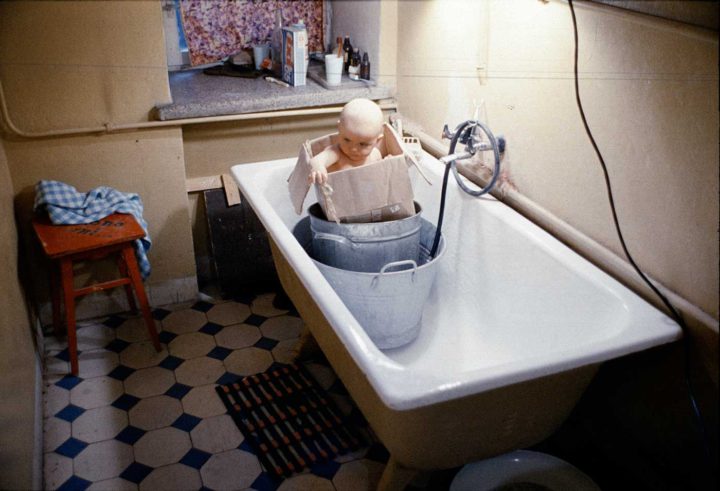

For instance, when the child is sitting in a stack of containers, they experiment with a matrioshka-like syntactic decomposition: ‘a child inside a box inside a metallic bin, inside a bowl, inside a bathtub, inside a bathroom…’ [Fig. 21].

Fig. 21 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

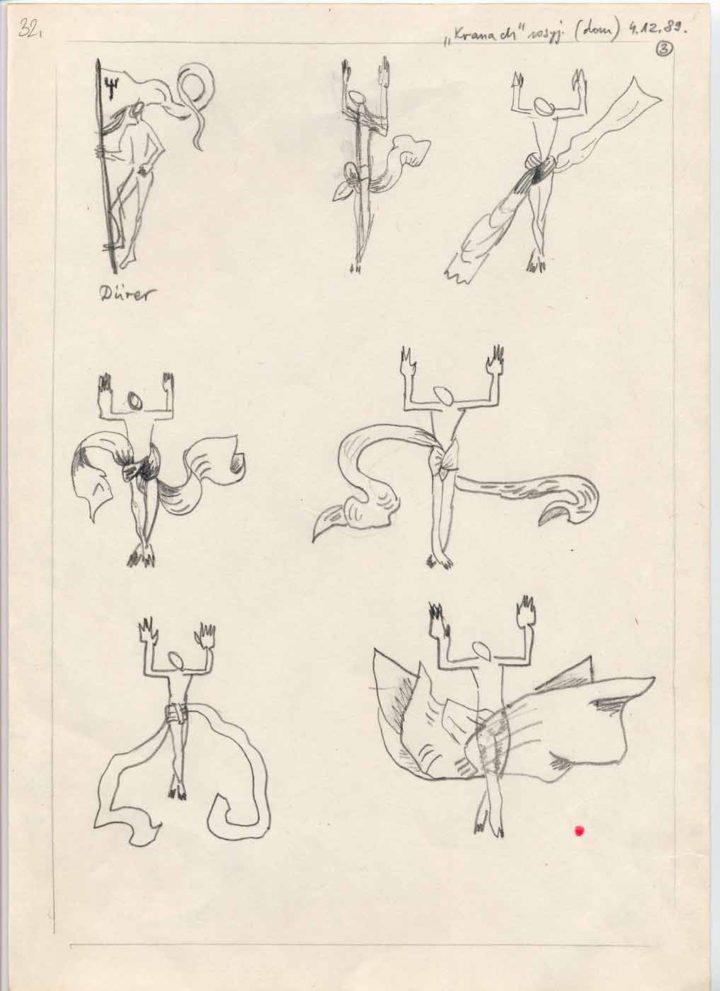

Obviously, the theory restrains the spontaneity of the recording of their daily life, all the more so as Kulik and Kwiek make preparatory notes and drawings before the photographic sessions [Fig. 22].

Fig. 22 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), Preparatory Notes for Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 22 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), Preparatory Notes for Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

During those sessions, the child is treated as an object; the theory dehumanises the relationship between Dobromierz and his mother. In my opinion, this theory functions as a metaphor of the state which moulds minds and impairs human links. Here, it is significant that the Communist regime encourages the diffusion of mathematical and logical theories, which thus appear as means of subjugation. Similarly, KwieKulik’s ornamental compositions – circles of onions or precious tangerines [Fig. 23] – add another degree of formal rigour. About her later photomontages, Kulik mentions the existence of “a relationship between an ornament and death” because ornament makes propaganda and religion powerful.

Fig. 23 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

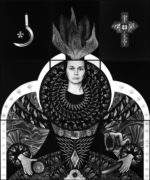

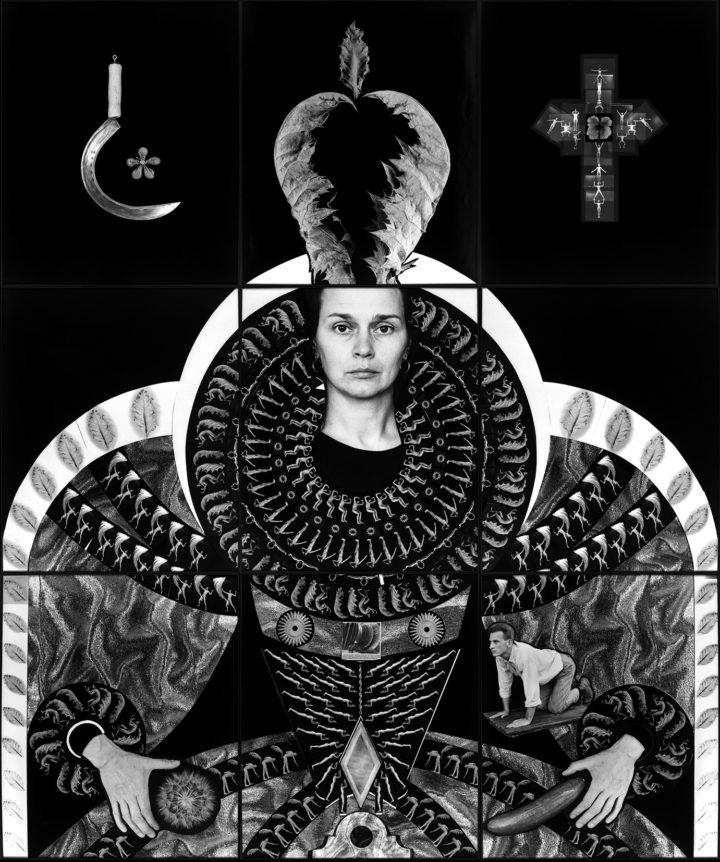

1 Zofia Kulik quoted in Piotr Piotrowski, ‘Between Siberia and Cyberia. On the art of Zofia Kulik and on Museums’, in From Siberia to Cyberia, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, p. 19, 1999. Moreover, she evokes the symbolic value of the circle, which surrounds her in all her self-portraits [Fig. 24 – Fig. 25], when she says “I feel like a prisoner inside the circle. I would like to represent myself without any circle but I can’t…” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007.

Fig. 24 – Zofia Kulik, Self-Portrait with a Flag from the series Mandalas, 1989

Fig. 25 – Zofia Kulik, The Splendour of Myself

In Activities with Dobromierz, one can see the same link between ornament and death – for it reminds one of black magic or religious ceremonies – and also between circle and subjugation [Fig. 26]. Moreover the child functions as a “human motif” subjected to the artist’s will. 1 Kulik created an exhibition called The Human Motif. See Zofia Kulik: The Human Motif, Zone Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1996. When Kulik evokes Libera, her model in her photomontages, she speaks about “a defenceless figure (…) totally subjected to [her]” and explains that “this defencelessness is emphasised by the black background, the empty space around the model, and the lack of any bearing.” 1 Interview with Marek Bartelik, pp. 4-5, Nov-Dec, 2006. Kulik subjects the naked and innocent baby to a series of Christ-like poses – echoing Polish nativity scenes – in the same way as she models Libera into poses from art history [Fig. 27 – Fig. 28]. Yet again, the relationship between the artist and her motifs can be understood as a transposition of the link between the State and its subjects. Communism reduces human beings to a role in society as if they were ornaments in a greater picture.

Fig. 26 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 27 – Zofia Kulik, from Archives of Gestures, 1987-91

Fig. 28 – Zofia Kulik, Sketches for the Archives of Gestures, 1987-91

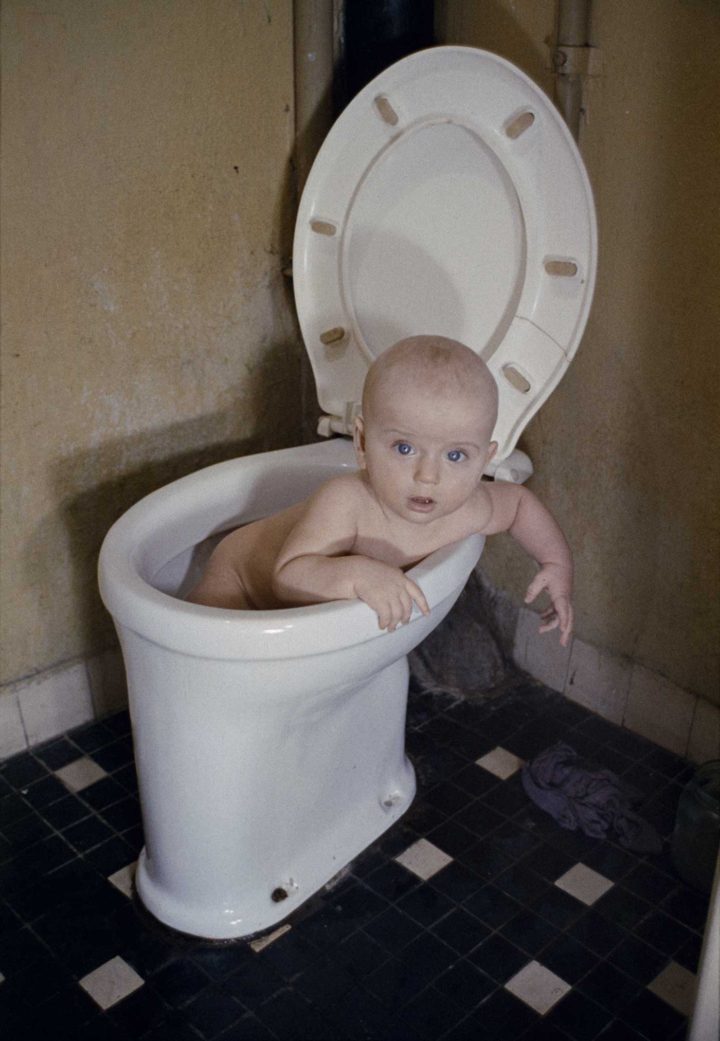

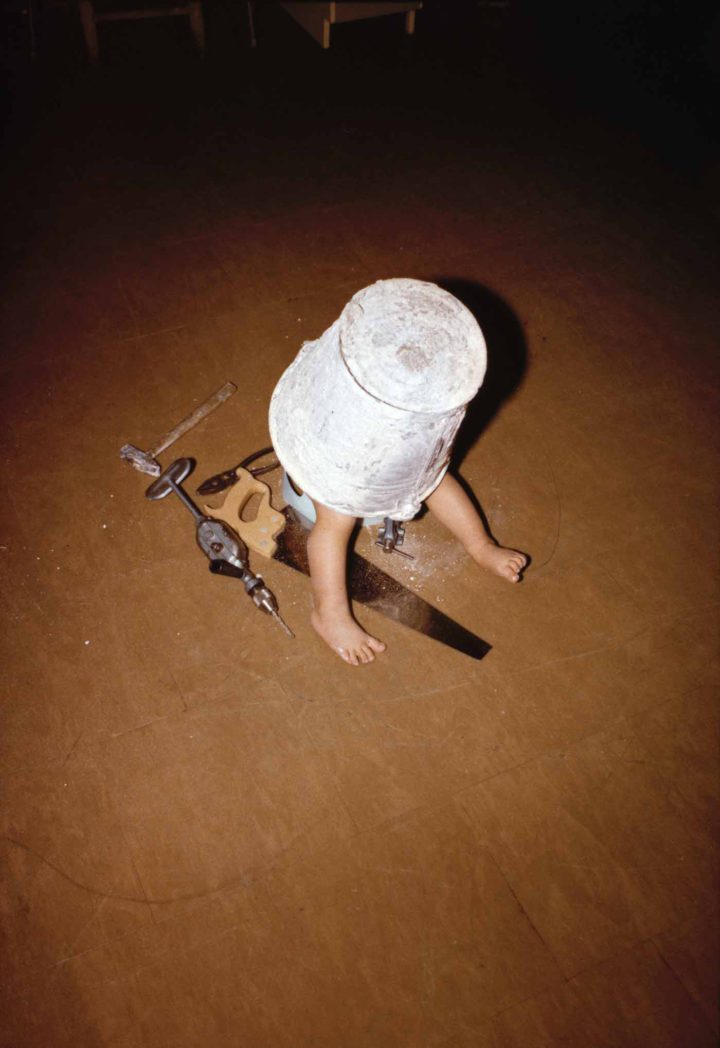

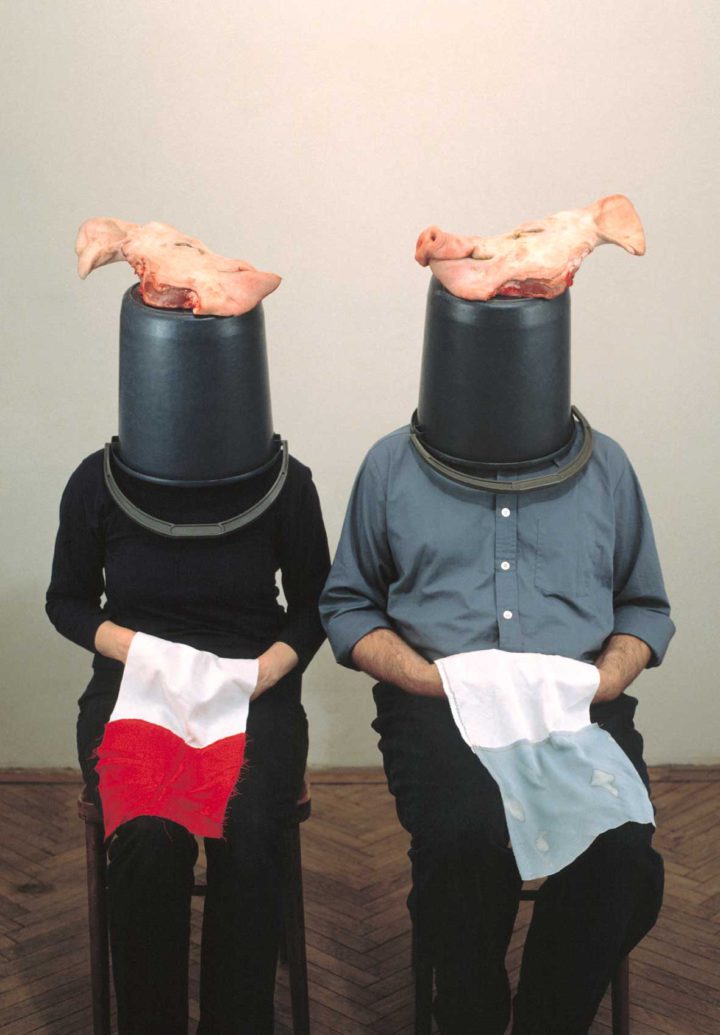

Some photographs raise the question of symbolic violence more than indifference. Indeed, sometimes it seems as if Kulik and Kwiek wanted to get rid of their child, flushing him down the toilet [Fig. 29], making him disappear under blankets [Fig. 30], or covering his entire head with a bucket [Fig. 31]. For Easter, the artists insert her son’s arm in the turkey and cover him with giblets [Fig. 32]. According to Kulik, the violence directed against her son “may be interpreted as a kind of revenge”. “I think we were treating him as were treated by the system, like objects.” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007. While the artist admits her sadistic attitude towards her son, she also explains that, during the photographic sessions, she attempted to protect the baby as much as possible and indeed suffered in her own body. 1 Zofia Kulik’s talk at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, Feb, 2007.

Fig. 29 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 30 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 31 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

Fig. 32 – Zofia Kulik (as KwieKulik), from Activities with Dobromierz, 1972-74

The violence expressed in the work is also directed against herself precisely because she agreed to submit her son to such treatments. This form of masochism echoes Kulik’s “personal repression (…) as she experienced [KwieKulik’s] performances as suffocating and drowning.” 1 Sarah Wilson, ‘Discovering the Psyche: Zofia Kulik’, in From Siberia to Cyberia, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, p. 55, 1999. In Banana and Pomegranate [Fig. 33], she wears a bucket over her head just as Dobromierz in one the photographs. Later, in 1977, Kulik used photographs of her son’s own “creations” (his childish drawings, his arrangements of objects) in the series Using Own Child in Own Art that she exhibited in her own apartment during seven years. By restoring his position as a subject, Zofia Kulik seemed to perform an act of contrition at the same time as she passed on the torch.

Fig. 33 – KwieKulik, Banana and Pomegranate [Hand Grenade], 1986. Galeria Dziekanka, Warsaw

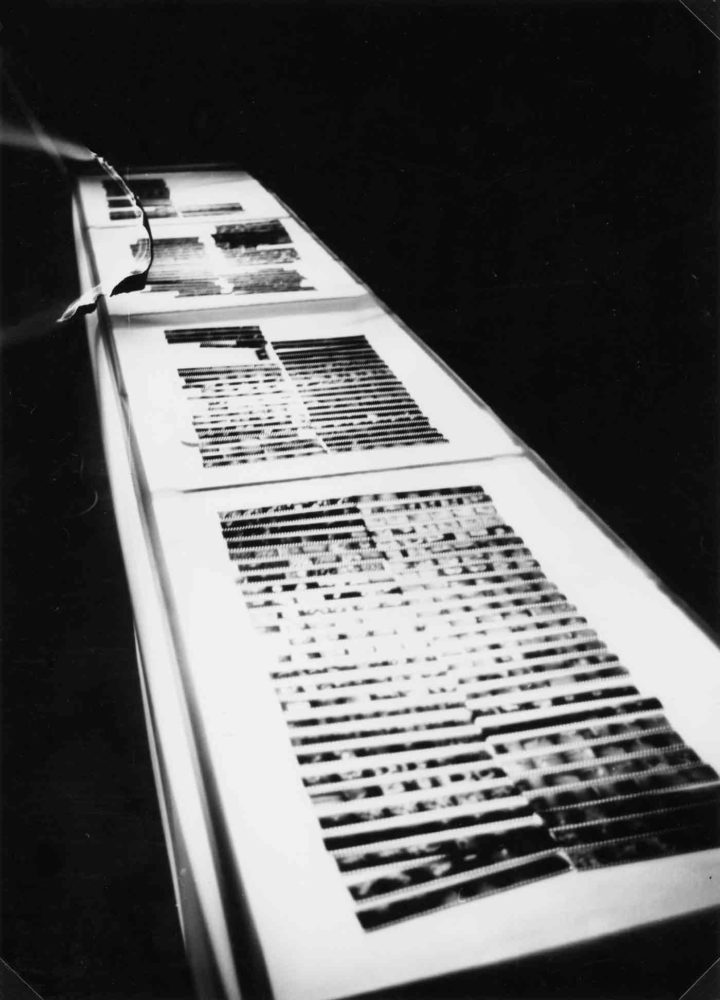

Obviously the situation in Poland was hardly as favourable. Even if the opponents of the regime did not suffer suppression comparable to that of the bordering countries, even if artists were conceded a certain freedom within proscribed limits (as long as they did not address social issues), they had neither recognition nor access to State-funding. In that context, Zofia Kulik exhibited the slide version of Activities with Dobromierz only twice: once at the Studio Gallery in Warsaw in 1973, and once in Malmö, Sweden in 1975. 1 Some slides of the series were also used in other thematic slide-shows, e.g. in late versions of Shades of Red. In 1975, the slides were exhibited unframed on back-lit tables [Fig. 34]. In 1973, the slides were placed between window panes, which “they took off their hinges in [their] flat as if in a display box.” 1 Interview with Maryla Sitkowska, Warsaw, 1986-1995. This presentation of Activities with Dobromierz entitled Logical Window (or Logical Lamp) [Fig. 35], was supplemented by political commentaries. 1 For instance: “PSP is degrading”, “If you are a young talented inquisitive artist, nobody will help you”… The whole exhibition layout appears to insist on the `home-made’ aspect in order to denounce the situation of Polish artists compelled to manage on their own. Kulik presented her work in the form of a slide show for the first time at the Courtauld Institute in London in February 2007.

Fig. 34 – Exhibition of the Activities with Dobromierz in Malmö (Sweden), 1975

Fig. 35 – Exhibition of the Activities with Dobromierz, entitled Logical Windows, in Studio Gallery, Warsaw,1973

Moreover, it is interesting to compare the relationship both artists maintain with their own work. In the late 1980s, Zofia Kulik experienced major upheavals both in her personal and social life. Indeed, the collapse of the communist system coincided with her painful separation from Kwiek. Consequently, Kulik, in an attempt to leave her past behind, refused to reconsider her work for several years. Nevertheless, the opening-up to the West, the discovery of psychoanalytic criticism and of feminist movements encourage her to revisit her artistic creations. Today, she questions the nature of her relationship with Kwiek and her child “I don’t know but maybe, if I treated my child that way, it was because I wanted to seduce Kwiek, I wanted to prove to him that I was an artist, an acrobat, someone with no fear.” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007. Kulik describes the role of the father in the separation with her son, which in a certain way parallels Kelly’s psychoanalytical interpretations. Nonetheless, whereas in Kelly’s work, the father is an abstract concept, Kulik refers to the flesh-and-blood father with all the seductive and sexual dimensions it implies. 1 It is interesting to point out that Kelly’s partner, Ray Barrie, is also an artist. However, he only figures once in Post-Partum Document, as the photographer of the frontispiece to the Post-Partum Document book. The picture shows Mary Kelly holding her son in front of her body in a manner suggesting a phallus. With Dobromierz, she now regrets the way she treated him, the lack of attention she paid to him and admits “to have been an unhealthy mother from the psyche point of view.” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007. Moreover, she examines her position as a woman in her “artistic couple” and realises the muteness which Kwiek drives her to. “We created some artistic creation the core of which was, for the most cases, a slide projection, a few gestures, but the commentary was the most important. Kwiek was the speaker. He explained things while I was sitting silent.” 1 Joanna Turowicz, The Rebellion of a Neo-avant-garde Artist, Interview with Joanna Turowicz, p. 8 Whereas Mary Kelly, using psychoanalysis, seems to look for an empirical verification of a preconceived theory, Zofia Kulik, with an inverse impulse, constantly questions her past works. Maybe this fundamental difference can explain Kulik’s attitude towards Kelly’s Post-Partum Document: “I need to force myself to adopt her way of thinking. I have the impression that you need to believe her as an author. I don’t see my work like that…” 1 Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007.

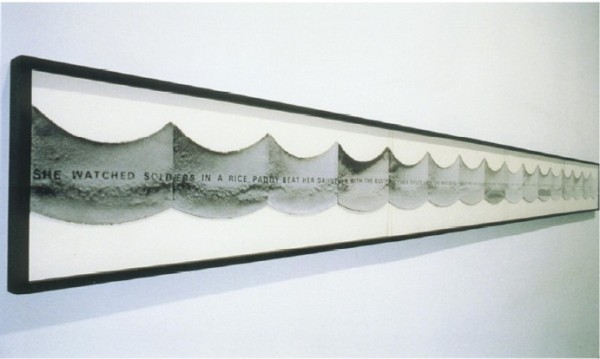

At the time when Mary Kelly and Zofia Kulik created their artworks about motherhood, they had no knowledge of each other’s practices. Indeed, Kulik discovered Post-Partum Document for the first time at the ninth Krakow meeting in 1981 and, according to her, she has only recently become interested in Kelly’s work. 1 See Sarah Wilson, ‘Discovering the Psyche: Zofia Kulik’, in From Siberia to Cyberia, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, pp. 53-73 1999; Interview with Maud Jacquin, Feb, 2007. And despite the increasing recognition of Eastern European artists in the West, one cannot attest that Mary Kelly actually knows Zofia Kulik. Yet, twenty years later, when Kelly created Mea Culpa (1999) [Fig. 36] and Kulik produced From Siberia to Cyberia (1998-2004), the two artists shared the same concerns again: the influence of the media on individuals who witness the atrocities of History secondhand.

Fig. 36 – Mary Kelly, Mea Culpa, Phnom Penh, 1975 (detail), 1999

Here, as in Post-Partum Document and Activities with Dobromierz, one can productively compare the contextual differences which imply different readings. The political history of Eastern Europe condemned artists to anonymity, including those who deserved a place in the history of art; this comparison comprises one part of a project to rectify this lack of recognition.

Bibliography:

Zofia Kulik

Zofia Kulik, From Siberia to Cyberia and other works, Museum Bochum, Kunsthalle Rostock, 2003.

K. Michalak, ‘Performing Life, Living Art: Abramovic/ulay and KwieKulik’, in Afterimage, Nov / Dec, 1999.

Sarah Wilson, ‘Zofia Kulik: From Warsaw to Cyberia’, in Centropa, a Journal of Central European Architecture and Related Arts, Science Press, vol.1, 3, pp. 233-244, Sept, 2001.

Exhibitions

Zofia Kulik: The Human Motif, Zone Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1996.

From Siberia to Cyberia, Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, 1999.

Architectures of Gender. Contemporary Women’s Art in Poland. Exhibition curated by Aneta Szylak, Sculpture center, New York, 2003.

“Fin Des Temps ! L’Histoire n’Est Plus”, L’Art Polonais du 20e Siècle, Hôtel des arts, Toulon, 2004.

Interviews

Maryla Sitkowska, Interview, Varsaw, 1986-1995.

Joanna Turowicz, The Rebellion of a Neo-Avant-Garde Artist.

Marek Bartelik, Interview, Nov / Dec, 2006.

Bozena Czubak, Self-Portraits. I Am, However, Myself not Somebody Else.

Ryszard Ziarkiewicz, Being Nothing But an Obedient Psycho-Physical Instrument.

Zofia Kulik, Talk at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, Feb, 2007.

Maud Jacquin, Interview, London, Feb, 2007.

Mary Kelly

Mary Kelly, Post-Partum Document, University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, 1999.

Mary Kelly, Imaging Desire, The MIT Press, London / Cambridge MA, 1996.

Mary Kelly, ‘Mea Culpa’, in October, 93, pp. 3-22, Summer, 2000.

Meredith Brown, An Activist’s Archive: Meaning and Materiality in Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document and Mea Culpa, MA essay, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2006.

Margaret Iversen, Douglas Crimp, Homi K. Bhabha, Mary Kelly, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, 1997.

‘Mary Kelly: Re-presenting the body’, in Psycho-analysis and Cultural Theory: Thresholds, St Martin’s Rress, New York, 1986.

Exhibitions

Mary Kelly Interim, Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, 1990.

Interviews

Juli Carson, ‘Mea Culpa: A Conversation with Mary Kelly’, in Art Journal, 58, no. 4, pp.74-80, Winter 1999.

Other

Zdenka Badovinac (Ed.), The Body and the East, from the 1960s to the Present, The MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 1998.

A. Chmielewski, Alina Szapocznikow’s Body of Work: Sculptures, 1953-72, MA dissertation, Courtauld, London, 2006.

Jacques Derrida, Mal d’Archive, une Impression Freudienne, Editions Galilée, Paris, 1995.

Janita Craw, Robert Leonard, Mixed-up childhood, Auckland Art Gallery, pp. 128-167, 2005.

Mihaela Frunza, Theodora-Eliza Vacarescu (Ed.), Gender and the (Post) ‘East’ / ‘West’ Divide Editura Limes, Romania, 2004.

C. Gopinathan Pillai, The political Novels of Milan Kundera and OV.Vijayan, A comparative study, Prestige Books, New Delhi, 1996.

Amelia Jones, the Feminism and Visual Culture Reade,r Routledge, London, 2003.

Amelia Jones, ‘Postmodernism, Subjectivity, and Body Art: A Trajectory’, in Body Art / Performing the Subject, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis / London, pp. 21-52, 1998.

Julia Kristeva, Au risque de la pensée, Editions de l’Aube, Paris, 2001.

Le XXe Siècle dans l’Art Polonais, AICA Press, Paris, 2004.

Therese Lichtenstein, ‘Images of the Maternal: an Interview with Barbara Kruger’, in Representations of Motherhood, Yale University Press, New Haven / London, pp. 198-203, 1994.

Kate Linker, Love for Sale: The Words and Pictures of Barbara Kruger, Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1990.

Dale Mendell, Patsy Turrini, The Inner World of the Mother, Psychosocial Press, Madison CT, 2003.

Charles Merewether, The Archive Book, Whitechapel / The MIT Press, London / Cambridge MA, 2006.

Laura Meyer, ‘Power and Pleasure: Feminist Art Practice and Theory in the United States and Britain’, in Amelia Jones (Ed.), A Companion to Contemporary Art since 1945, Blackwell, London, pp. 317-342, 2006.

Fred Misurella, Understanding Milan Kundera: Public Events, Private Affairs, University of South Carolina Press, 1993.

Helen Molesworth, ‘House Work and Art Work’, in October, 92, pp. 71-97, Spring, 2000.

Opus International – Edition Spéciale Pologne, 6, April, 1968.

Dorothea Olokowski, Gilles Deleuze and the Ruin of Representation, University of California Press, 1999.

Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Framing feminism: Art and the women’s movement. 1970-85, Pandora, London, 1987.

Ines Rieder, Feminism and Eastern Europe, Attic Press, Dublin, 1991.

Renata Salecl, The Spoils of Freedom, Psychoanalysis and Feminism after the Fall of Socialism, Routledge, London, 1994.

Alina Szapocznikow, Capturing Life: Drawings and Sculptures, IRSA Fine Art “Hôtel de Saxe”, Cracow-Warsaw, 2004.

Ann Taylor Allen, Feminism and Motherhood in Western Europe 1890-1970, Palgrave Macmillian, 2005.

Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-garde, 1880-1990, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC, 1991.

Sarah Valdez, ‘Mary Kelly at Postmasters’, in Art in America, 87, pp. 125-126, September, 1999.

Sharon Wolchik, Alfred G. Meyer, Women, State, and Party in Eastern Europe, Duke University Press, 1985.