Afterimage, 16 November/December 1999

Katarzyna Michalak

Performing Life, Living Art: Abramovic/Ulay and KwieKulik

Artistic couples are not a common phenomenon when artistic activity fuses with private life. There has been, however, growing interest in this kind of collaboration since the 1970s and it is not accidental that it coincided with the development of performance and body art. The physical action and bodily interaction emphasized links between life and art. Two couples that embodied the paradigm of close collaboration were Marina Abramovic and Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen), known as Abramovic/Ulay, and Zofia Kulik and Przemyslaw Kwiek, known as KwieKulik. Both couples were active during the same period (KwieKulik 1971-87, Abramovic/Ulay 1976-89) and both engaged in performance and body art. Differences in their work can be understood against the social, political and cultural contexts of the time, as well as their particular situations.

Although of different nationalities and different political systems, Abramovic/Ulay did not stress this polarization in a political context (an exception is Communist Body/Capitalist Body, Amsterdam, 1979) but rather in a universal context as opposition between east and west, male and female. They acted between unity and separation. Ulay explained their relationship: “We begin in a sort of synchronized similitude … and then we arrive at the level in which each of us functions alone. The two bodies doing the same, but within, there is a separation.”1 Bojana Pejic, ‘Being-in-the-Body: On the Spiritual in Marina Abramovic’s Art.,’ in Marina Abramovic and Friedrich Meschede, ‘Marina Abramovic’ (Stuttgart: Edition Cantz, 1993), p. 33. There was no such tension with Kulik and Kwiek who were both from Poland and graduated from the same art school in Warsaw. Their activity was less concerned with personal issues than with Poland’s national politics of the 1970s and ’80s. Comparing the constructs of their names further illustrates the basic differences between the duos. Abramovic/Ulay, written with a slash, emphasizes the poetics of polarization present in their art, while KwieKulik, with a shared “K,” stresses the close collaboration and even mutual dependence of the couple.

The body as a place of exploration was seen as female domain in the early ’70s. For male-female artistic couples the decision to be involved in body art challenged the code of masculinity and, as Michael Fried recognized, the ‘specifically feminizing debasement of virility of “pure” modernism.’ 1 Amelia Jones, ed., ‘Body Art: Performing the Subject’ (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), p. 112. This critical approach is even stronger in the case of homosexual couples like Gilbert & George, where the codification of masculinity is shaken, or Eva & Adele, where biblical Adam is supplanted by cross-dresser Adele and traditional masculinity is denied.

Gender issues are central for Abramovic/Ulay who question such perceived masculine traits as domination and strength. Their performance Incision (Graz, 1978) was based on male-female opposition. Abramovic stood motionless during the performance while Ulay, naked, tried to run against the restriction of an elastic band fastened around his waist and attached to the wall. Abramovic represented passive femininity; Ulay represented male activity. With this performance they raised the question of mental and bodily freedom. Ulay worked from an active position although he was physically limited. His mind was free and forced his body to challenge the restrictions placed upon it. His body moving forward and backward created an incision in space. Abramovic’s passivity represented the traditional societal position of women as non-active entities.

Other pieces proposed a model of balanced gender, especially visible in their symmetrically arranged performances. In Imponderabilia (Bologna, 1977) the couple stood naked against the walls of the narrow entrance to the gallery facing each other. In order to enter, the public had to decide whether to turn to face him or her and thus choose their own gender subjectivity. In Relation in Space (Venice, 1976) their naked bodies crashed into each other at higher and higher speeds. Both took active positions in this performance and presented themselves as equal by exerting the same physical strength. Like Imponderabilia, these symmetrical performances fused their two bodies into one symbolic whole. In Breathing In/Breathing Out (Belgrade, 1977) they inhaled and exhaled carbon dioxide from each other’s mouths with microphones affixed to their necks in order to broadcast the inner pulse of their bodies. ‘In the beginning of their collaborative work they often spoke of themselves as an androgyne, as an alchemical image of a two-headed body, “says art critic Bojana Pejic 1 Pejic, p. 34. It seems Abramovic/Ulay did not undermine the privileged position of man but, rather, as Amelia Jones states,” veil[ed] it in what is in effect experienced as a bipolar model of gender.’ 1 Jones, p. 141.

This gender perspective was also present in another performance piece entitled Talking About Similarity (Amsterdam, 1976) which was based on exchanging roles. At the beginning of the performance Ulay sewed his mouth shut, giving up his freedom of speech. Abramovic sat next to him and answered questions put to Ulay by viewers. She took over his subjectivity by appropriating the pronoun ‘I’ as if she were Ulay, but in doing so, she lost her own identity. This shift in subjectivity was intended to challenge male-female roles, showing woman as having control of the words and man without a voice. Instead, it reinforced gender stereotypes showing woman as the passive partner who speaks, but only from the position of an assumed male identity. The male-female relationship was less significant for KwieKulik because they did not base their performances on gender distinction. In some cases they even hid their gender identity—in ‘The Banana and the Pomegranate [the Hand-Grenade]: Reistic Theater’ (Warsaw, 1986), for instance, their heads were covered with pails. As a result they were recognized only as human beings, not as a man and a woman.

KwieKulik, Banana and Pome-grenade, scenes from the performance, reconstruction made without an audience in the house in Dąbrowa after the public show in Pracownia Dziekanka, 1986

The only performance that opened itself to analysis from a gender perspective was Activity for the Head (Lublin, 1978), a three-piece performance. In the first scene, the artists sat on the floor with their heads sticking out of holes in two seats of a row of chairs.

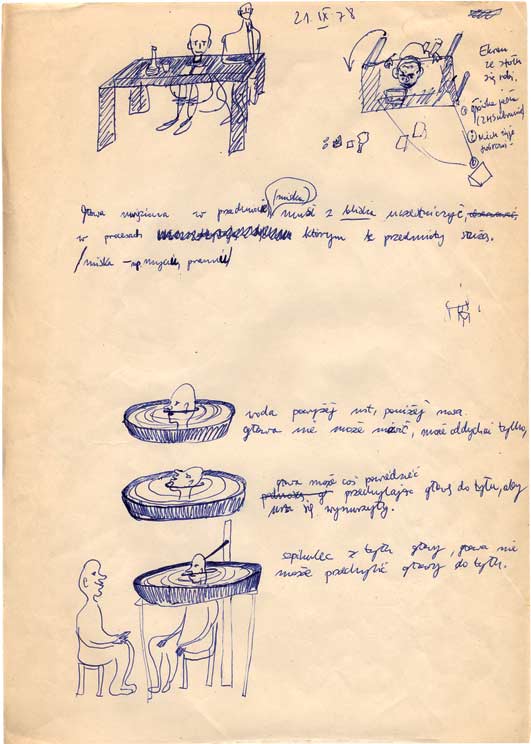

KwieKulik, sketches and notes concerning the performance, Activities for the Head, 21.09.1978

In the next scene, Kulik sat on the floor with her head sticking out of a hole in a wash basin. Kwiek poured water into the basin until Kulik could barely breath through her nose and then washed the upper part of his body and legs with the water while shouting, ‘Say anything, wretch!’ The performance ended with both artists sitting on chairs with their heads covered by garbage pails. Although the first scene could be considered in a gender context because it emphasized male power, the whole performance diluted this perspective by stressing the political context. The term “activity on the head” is an allusion to political indoctrination in Poland.

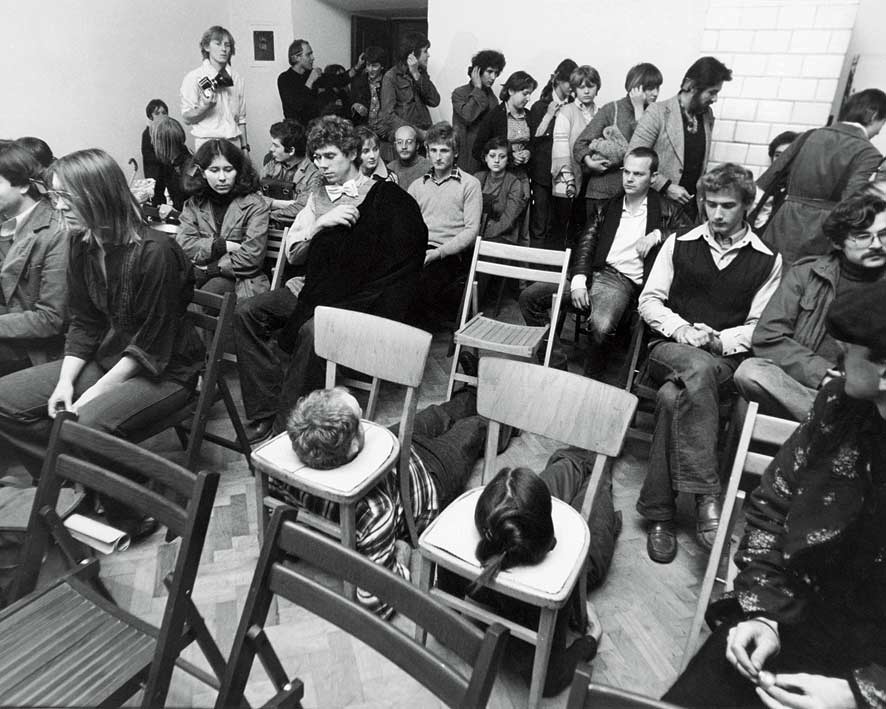

KwieKulik, Activities for the Head: Tree Acts, ‘Performance and Body’, Galeria Labirynt, Lublin, 13.10.1978; photographs by Andrzej Polakowski

Because both couples experienced cultural and political limitations in their lives, the concept of freedom was critically examined in their work. In 1986 KwieKulik performed a piece called Arcady (Warsaw), in which they used a chain as a metaphor for mental repression. Kwiek and Kulik hung two paraffin lamps on a gallery wall. A chain was placed on a hook hung just below, which was covered with a paper hand to appear as if the hand held the chain. The artists then put two collars around their necks that were affixed to both ends of the chain. Kwiek and Kulik went forward: he shouting ‘dick’, she shouting ‘ass’, but the length of the chain limited the movement of their bodies and the tight collars caused their words to become clogged in their throats. Freedom of movement and freedom of speech were controlled and limited by the paper hand, a symbol for invisible power. With this performance, KwieKulik expressed the idea of power as the invisible control of human activity. Arcady, the land of eternal happiness, is ironically a place where invisible power limits movement and speech. Although this work referred to power strategies in general, the primary system being commented on was communism, which KwieKulik experienced in their everyday lives.

KwieKulik, Arcadia; scenes from the performance, reconstruction made without an audience just after the public show in Pracownia Dziekanka, 1986

The communist system, as all totalitarian systems, appealed to the metaphor of the body. ‘This language contained many “biologistic” metaphors such as “the body of the institution,” “state organs,” or “the hand of justice”, said Pejic. 1 Pejic, p. 31. It is significant that both totalitarian discourse and performance artists use the metaphor of the body. For the former, the body is a universal but abstract model of society, while the latter insist on their own individual and concrete bodies.

Abramovic/Ulay adopted a similar perspective in their performance Communist Body/Capitalist Body. This work was a celebration of their shared birthday (November 30). They invited friends to a private home in Amsterdam and prepared two tables: one with food from a communist country, the other with food from a capitalist country. During the length of the performance both artists slept in beds in the same room where guests celebrated the birthday. Their birth certificates hung on the wall, illustrating that Abramovic was born in communist Yugoslavia and Ulay in fascist Germany. The terms ‘communist body’ and ‘capitalist body’ appealed directly to the artists’ bodies as products of concrete political systems that tended to control not only mental identity but bodily functions as well. Both artists were born under totalitarian systems that tried to use the body as a living sculpture. In this context Robert R. Taylor writes about ‘human architecture’ which was a domain of Nazi propaganda masters for whom ‘the people are neither more nor less than what stone is for the sculptor’.1 Michael North, “The Public as Sculpture: From Heavenly City to Mass Ornament,” in W. J. Mitchell, ed., ‘Art and the Public Sphere’ (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 16. By the term “human architecture” Taylor means using the mass of people for propaganda purposes when human beings disappear as individuals. However, the interest in shaping human architecture cannot only be attributed to totalitarian systems. Eric Hobsbawm states that after 1914 in France, Germany, England and the United States “the emphasis shifted from statuary to great empty urban spaces in which massed crowds were to provide the aesthetic impact”. 1 Ibid, p. 17. Communist Body/Capitalist Body is the only work in which Abramovic/Ulay made such a polarized political statement. Abramovic/Ulay came to the conclusion that private bodies exposed to manipulation by a system become public bodies and, in consequence, political bodies. Manipulated bodies change from subjects into objects of power.

Abramovic/Ulay presented themselves as products of a political system while KwieKulik debunked the objectifying strategy of power when they appeared as objects in their performance ‘The Banana and the Pomegranate [the Hand-Grenade]: Reistk Theater’. 1 In Polish the same word is used for pomegranate and hand grenade. It was impossible to keep this double meaning in the English translation, so the other meaning is given in parentheses. Reistic Theater is a derivative from Latin: “res” meaning “thing” in the meaning “theater of things,” a theater where things enact all roles. It consisted of 11 static scenes. The artists sat on chairs next to each other, their heads covered with pails. Different objects were used in each scene, either in the artists’ hands or resting on the pails on their heads. A curtain decorated with silver stars and moons hung behind the couple which, combined with the title, suggested comic action that dramatically contrasted with the gloomy scenes.

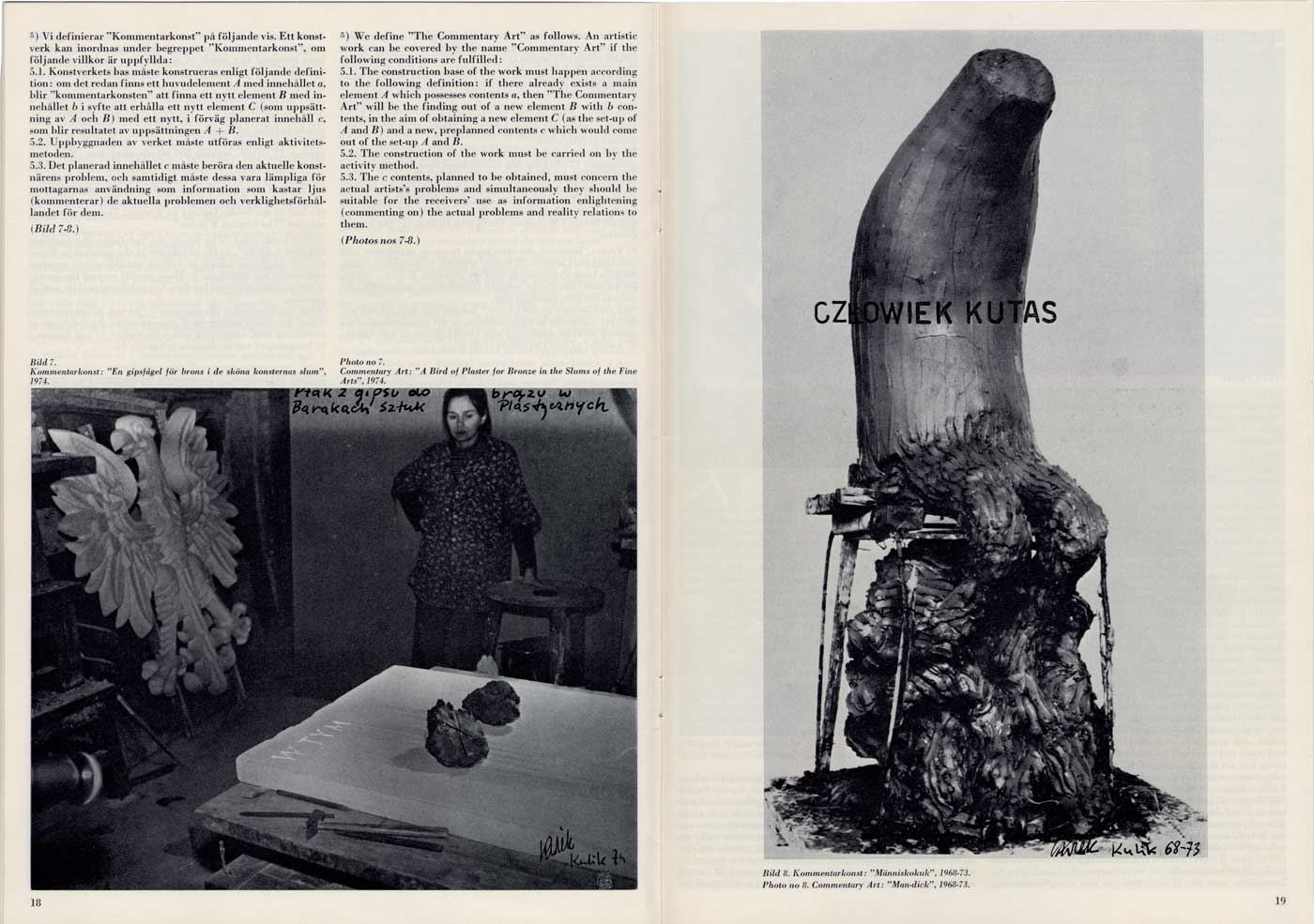

The objects in the piece were like scraps of reality that appeared as signs or symbols of the different activities of everyday life. In one scene bread and glasses sat on the pails while the artists each held a hat and a bottle of vodka. In another scene, the artists’ passport photographs were placed on the pails while mirrors reflected the artists’ hands. The mirrors were an allusion to surveillance and the passports addressed the personal experiences of the couple, who were deprived of their passports for four years after an exhibition in Sweden 1 In 1975 KwieKulik participated in the exhibition “7 Young Poles: Environments and Activities” at the Konsthall in Malmo, Sweden. In the exhibition catalog they included two pictures from the series “Commentary Art”. One depicted a large plaster eagle—a Polish emblem—with the comment, “A Bird of Plaster for Bronze in the Slums of the Fine Arts” The other showed a sculpture entitled ‘Man-dick’ which the Polish authorities understood as a criticism of the Polish political realities. They subsequently prohibited KwieKulik from representing Poland in any foreign exhibitions, which meant that they were deprived of their passports.. In some scenes they used national symbols in a derogatory context, such as the Polish emblematic eagle made of soap situated next to a sugar lamb, a lowbrow symbol of Catholicism. The fact that they were made from non-durable materials shows the impermanence of the ideas they represent. By visually concealing the artists’ heads, the pails denied subjectivity; in this “theater of things” the main roles were instead enacted by objects. The sequence of static scenes functioned almost as photographs. This non-active performance presented an inertia of society symbolized by the artists’ inaction.

Layout of two pages in printed catalogue: photograph with the eagle called A Bird of Plaster fot Bronze in the Barracks of Fine Arts was placed by the Swedish designer next to the Man-Dick, both works from the Commentary Art series

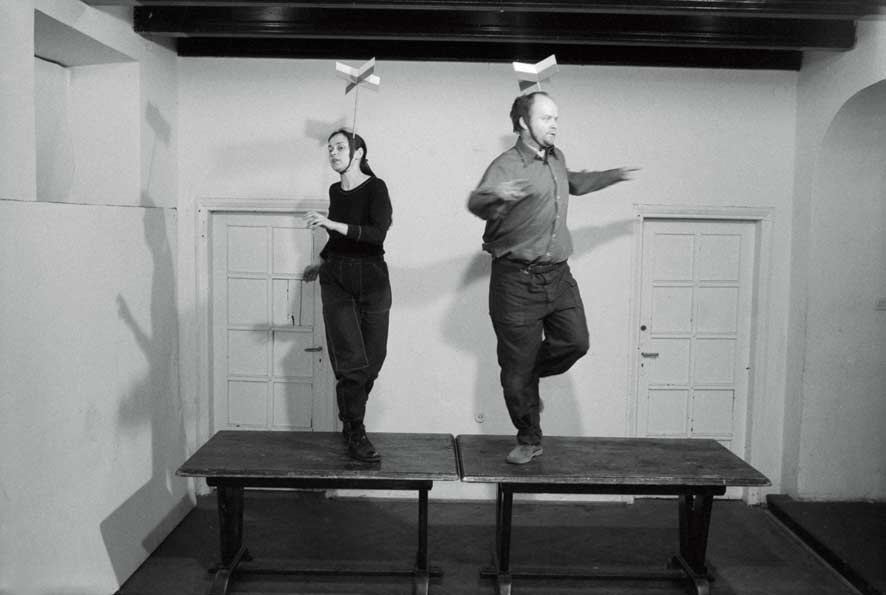

In Polish Duet (Warsaw, 1984) KwieKulik criticized the political system and authorities by using irony to ridicule national symbols. They created absurd situations relating to the Polish flag. In the first scene, the artists simulated airplanes attempting to take off to realize their dreams of crossing borders. Polish flags were fixed to their heads as propellers. In another scene the artists faced each other holding a red and white flag.

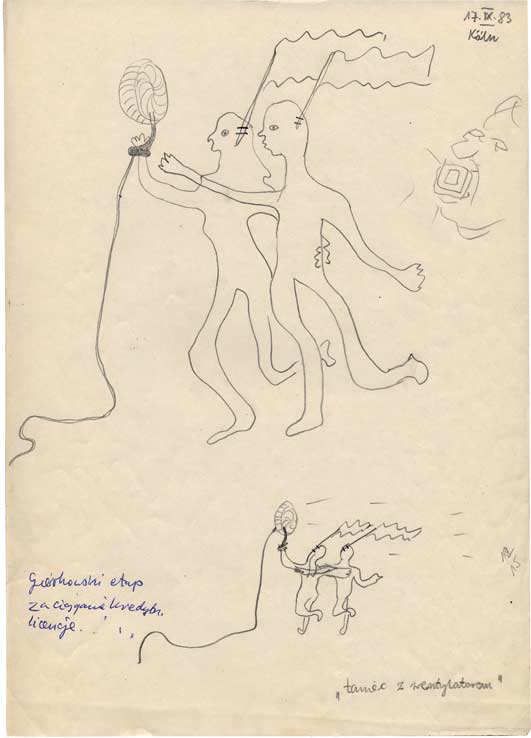

Zofia Kulik, sketches and notes for the performance Polish Duo 1

The flag had a staff on each side, and Kulik and Kwiek each held one. Both artists began to move backward in opposite directions until two white and gray flags emerged from under the red and white one, which fell to the ground. The gray flags disclosed a drab truth hidden behind a colorful symbol.

KwieKulik rolling with flags on a long table or spinning around on their own axis, performance Polish Duo 1, Pracownia Dziekanka,1984

The Polish couple criticized state authorities by discrediting national symbols and ridiculing the absurdity of reality. In the 1980s the most basic foodstuffs (butter, meat, sugar) were available only with ration cards. This situation was addressed in the performance ‘Festival of Intelligentsia’ (Lublin, 1985), in which KwieKulik tied loin chops (a product in short supply) around their waists and heads. They laid down on a large box facing each other. Their heads were covered by a cage with a cat inside. Eventually the cage was shrouded in black fabric with the phrase “Festival of Intelligentsia” printed on it. It looked like the funeral of the intelligentsia. KwieKulik disclosed the mental impoverishment of the Polish society where higher intellectual purposes were dominated by down-to-earth needs, like obtaining food.

KwieKulik, scenes from the performance Festival of the Intelligentsia, Pracownia Dziekanka, 1986

KwieKulik performed multi-piece performances with complicated symbolic meaning. They deliberately exploited aspects of theater, manipulating elements of tragicomedy or farce. They built metaphorical meaning and psychological distance into the roles they enacted, manifesting themselves not as active subjects but rather representing their presence within the political restrictions of communist Poland. Abramovic/Ulay used simple repeated actions like the inner pulse of the body; the actions were a manifestation of the bodily presence. Abramovic described it as, “Being-in-the-body, here and now.” 1 Pejic, p. 26.

The opposition between presence and representation is visible in both couples’ approach to photography in the context of performance. For performance artists, photography is one of the few possibilities available to substantiate performed action. Some artists treat it as a necessary evil because although it provides permanent documentation of the action, it denies the fleeting quality of performance. Abramovic/Ulay used photography as a document, not as an independent artistic medium. All pictures taken during their performances show the whole event from the audience to the often insufficient lighting to the performance space. The photographs deliberately emphasized the inability of photography to accurately convey the intimacy of the performance. (They also made videos of their pieces which were more appropriate for documenting some of the violent movement that created a special tension in the performance, impossible to capture in a static scene.)

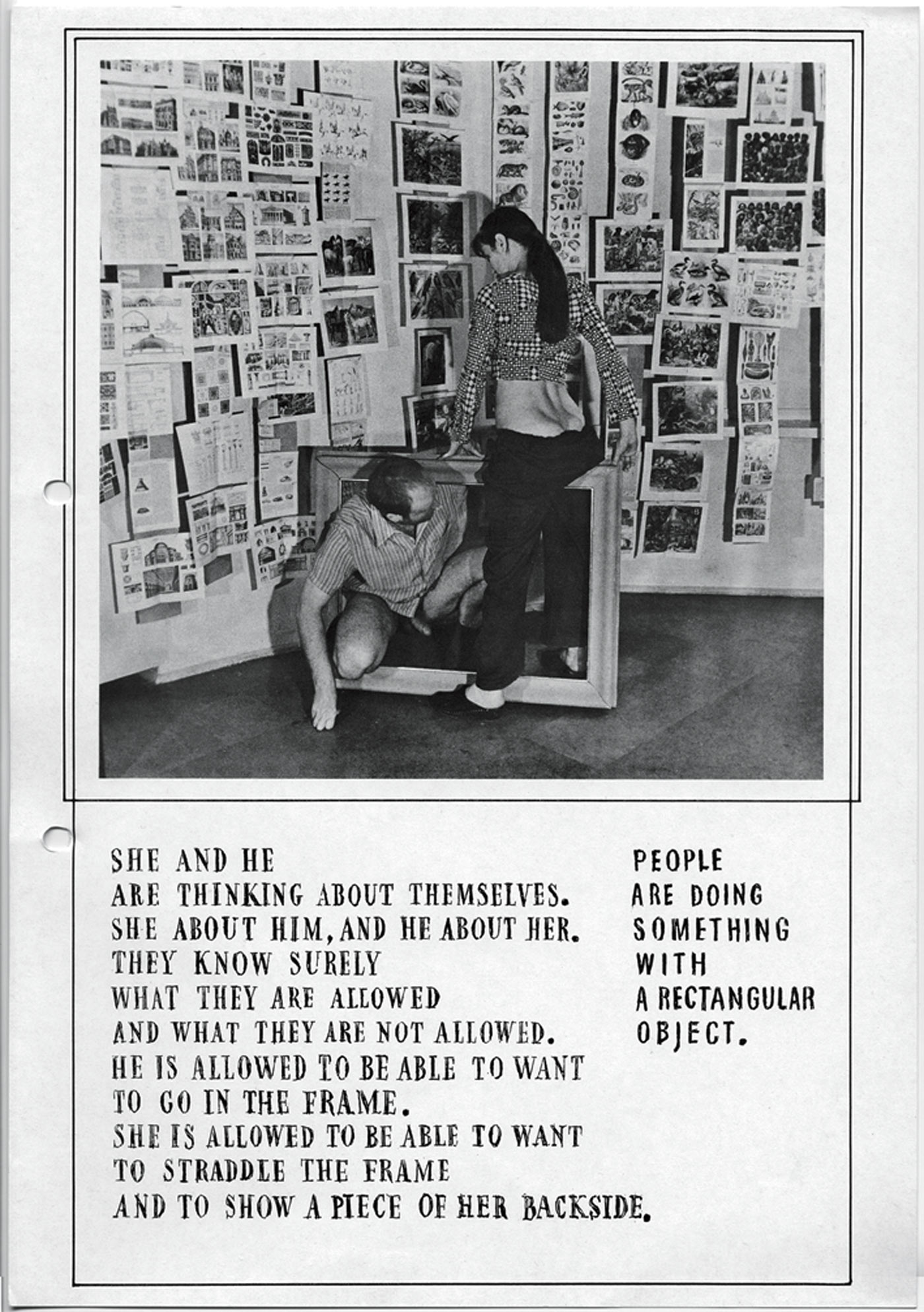

KwieKulik, however, treated photography and performance as equally important artistic creations that are accomplished together: one action included many creations. They used photography not merely to document a transient event but also to create “aesthetic time results” that were photographs made after the original performance. Multi-piece performances were organized on the model of slide projection, in which one scene follows another. Curtains replaced the opening and closing of the shutter. Large Cibachrome photographs of these performances were shown at KwieKulik exhibitions. Sometimes, by mixing photographs from different performance pieces, the artists created a new object. In 1984 at Warsaw’s Dziekanka Gallery, they used photographs and Polish flags to create a kind of altar, similar in decoration to communist propaganda banners. Photography also had additional importance for KwieKulik, living in isolation in communist Poland, because it could represent them abroad. Photographs from the non-public performance ‘Activity with the Frame’ (1977), showing the artists in various sexual situations involving a picture frame, were printed in the German publication Reaktion 5 1 Reaktion 5 (Alsbach, Germany: Verlaggalerie Leaman, 1980)..

KwieKulik, Activites with a Frame, 1980

Abramovic/Ulay stressed direct bodily contact with each other. Each performance was a kind of personal trial to redefine their relationship, which was not completely defined or stabilized to begin with. To emphasize the real action they never used a script and moreover they never repeated a piece. In fact, I would say Abramovic/Ulay never performed for the public, since the relationship between the couple and the viewer was always of secondary importance when compared to the relationship between the artists themselves. They resolved to perform regardless of audience presence at their performances.

It is significant that in the beginning Abramovic/Ulay used violence and aggression as performative tools for testing and establishing the boundaries of their bodies and of their relationship. All actions were dynamic and performed at high speeds such as in ‘Relation in Space’, where they crashed their naked bodies into one another. However, their later actions were completely opposite. ‘Nightsea Crossing’ (1981-86) was realized in different places all over the world. In each performance, for 90 (nonconsecutive) days the artists sat motionless for several hours each day. They minimized any physical movement and refrained from eating in order to decrease biological functions. The aggression used in early performances was not parallel to their personal relationship. On the contrary, the evolution from dynamic performance to the near abandonment of action is indicative of the crisis in their personal relationship, which escalated during the peaceful period of their artmaking.

Unlike Abramovic/Ulay, KwieKulik did not address their relationship in the context of their performances, instead choosing to confront the viewers with a representation of scripted ideas. KwieKulik always established a relationship between one another when they entered a scene, whereas Abramovic/Ulay were always trying to establish this relationship while the viewers watched.

“There was no space for private life. Everything was public life,” said Abramovic in 1998 about her collaboration with Ulay 1 Katarzyna Michalak, “Marina Abramovic: Transitory Objects” in ‘Magazyn Sztuki/Art Magazine’, no. 19 (March 1998), p. 46.. Presenting this tension between art and life was the most important issue for the couple. They blurred the distinctions between real life and art, erasing cultural codes that determine the border between the real and the artificial. They tried to keep aesthetic qualities to a minimum. In their early pieces they performed naked in order to publicly reject the cultural context responsible for separating art from life. They believed that the naked body could be neutral and they used it to manifest the presence of subject instead of the representation of subject that dominated earlier art and theater.

They stressed biological, instead of mental, activity. They performed simple, bodily actions: shouting, breathing, slapping. By pushing their bodies to biological limits they defined themselves as physical and not purely intellectual beings. There was limited use of spoken language—a cultural product—with mostly simple, innate sounds instead. This stage “before language means that the artists never defined their identification but, as suggested earlier, each performance was an attempt to reach it.

The interrelation between art and life was realized by Abramovic/Ulay strictly in the field of body art. KwieKulik were interested in multi-media activity. Besides performances, they made photographs, installations, drawings, sculpture and mail art—always stressing the process of creation. For KwieKulik intimacy between art and life meant that reality became the direct material as well as the context for their art. They often used gray paper to signify the grayness of everyday life in Poland. The aim of their art was not to embellish reality.

Art was a tautology of reality and grayness that captured different fields of life: ideology—symbolized by the gray flag in ‘Polish Duet’, art—embodied by gray canvas on which the artists placed underwear for ‘Art in Panties’ (1978); and reality—illustrated in ‘Moods: Gray Paper’ (1984), in which the gallery space was wallpapered in gray.

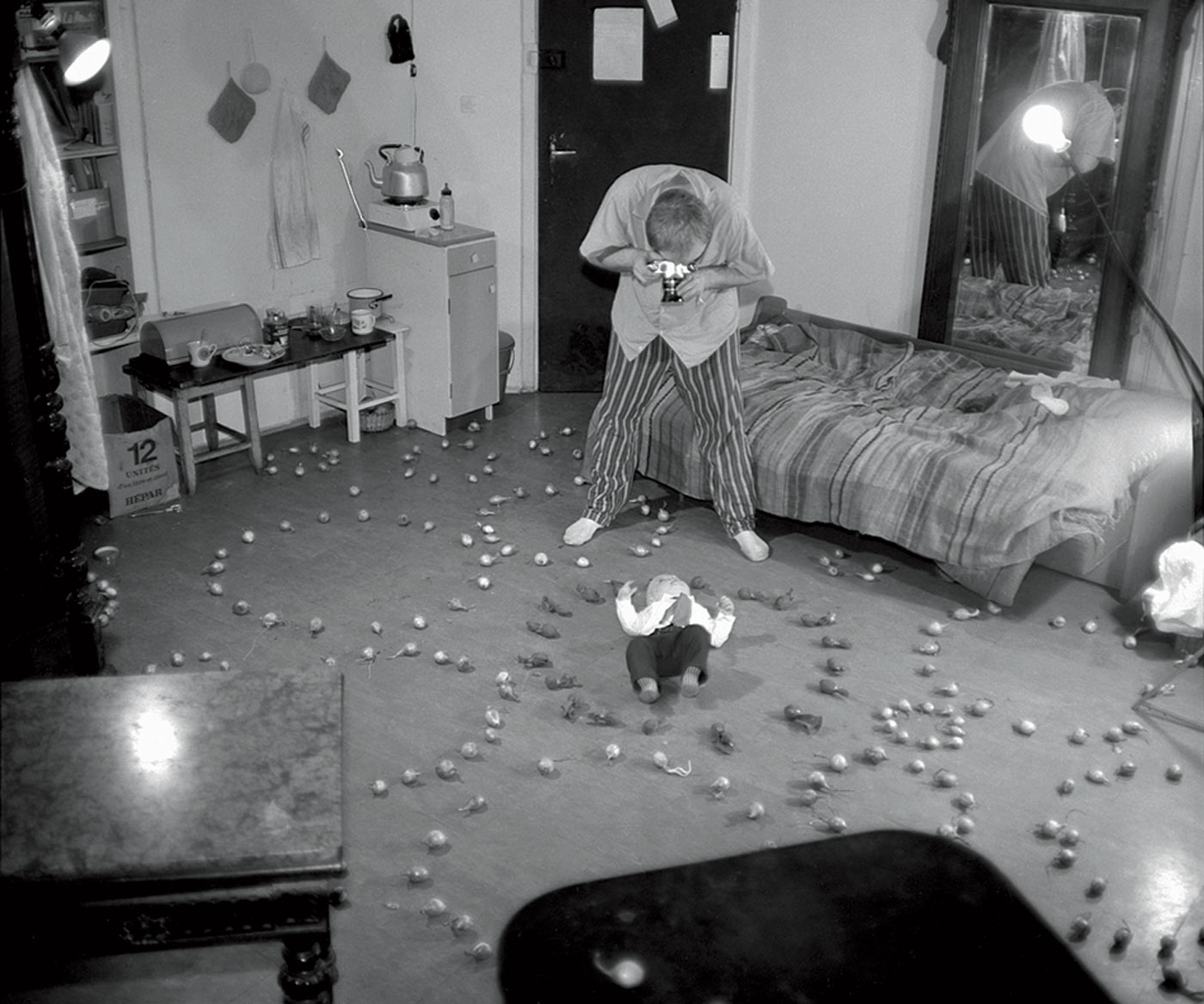

From the series Activities with Dobromierz (I) (1972-74) by KwieKulik

Reality as a source of artistic inspiration also included its effect on their personal states of mind. “Art From Nerves” and “Art On The Run” are watchwords the artists used to describe the conditions in which they created their work. KwieKulik, similar to Abramovic/Ulay, did not treat their private life as a safe enclave separated from art. KwieKulik included their son, Dobromierz, in their art projects from his birth. ‘Activities with Dobromierz’ (1972-74) was the general title of several performances in which Dobromierz was a main element. The artists took pictures of their son in different situations, partly created by everyday reality, partly arranged by the artists; Dobromierz in a toilet bowl, with a pail on his head or lying on the floor amid a circle of knives and forks. In 1973 slides documenting these activities were exhibited in a frame fashioned from a window brought to the gallery from the artists’ house. The window was a symbolic frame for actions that occurred on the border between reality and art.

In the late 1980s both couples decided to split on both personal and artistic levels. If we look at each relationship in a historical perspective we can see that their dissolutions coincided with the crisis of performance art in the 1980s, when body art was considered as fetishized object of the male gaze and increasing commercial tendencies of the art market caused a return to large-scale oil paintings. At that time both couples experienced difficulty in finding methods of expression.

Collaboration in artistic couples, where art and life fuse into one, questions the possibility of maintaining the creative relationship when the emotional one has collapsed, as shown in the examples of KwieKulik and Abramovic/Ulay. In the case of Abramovic/Ulay the relationship began to spoil “on a strictly personal, emotional and psychological level”, as Ulay claims, “It was never because one of us didn’t agree with the work. But in the end the work started sufferinig from the change, of course.” 1 Paul Kokke, “An Interview with Ulay and Marina Abramovic”, in ‘Ulay/Abramovic: Performances 1976-1988’ (Eindhoven: Stedelijk Van abbemuseum, 1997), p. 118.Their last collaborative project was ‘Great Wall Walk’ (1988), three months of walking on the Great Wall of China. Abramovic began from the east, Ulay from the west. Their meeting point in the middle of the wall was also the point where they ended their common private and artistic life. Said Abramovic, “We didn’t talk anymore, we even had two [separate] press conferences after it. It was a very painful experience and it took me a lot of time to really get over that feeling of complete failure.” 1 Michalak, p. 46. This project most dramatically blurs the distinction between art and life. Ulay noted, “I wanted to break the image of being an institution and break the ideology of being a special couple. I couldn’t agree with it anymore.” 1 Kokke, p. 117.

The parting of Kwiek and Kulik occurred in 1987 after they felt that they had exhausted all ideas and needed a new language of artistic expression. Kulik said, “Finally, the dialogue in the duo became a thing in itself. A realization of a work, i.e., communicating to others your own idea, lost importance. I felt bad. I felt the need for a silent consideration more and more strongly, indeed self-surprises with my own non-verbal decisions, an immediate dialogue with a work so that the work gave me a hint what to do next by its own response.”1 Zofia Kulik, “Commentary”, in ‘Magazyn Sztuki/Art Magazine’, nos. 15-16 [3-4/97], p.223. Their moment of separation coincided with the collapse of communism in Poland and was in part an effect of the changing political situation. For Kwiek and Kulik regaining political freedom meant regaining personal freedom as artists as well.

The artistic activity of the couples, as well as the reception of their art, should be considered from the perspective of their respective geography. Political division in Europe situated them in different contexts. Abramovic/Ulay’s use of universal language to describe both gender and political problems could be understood in Austria, Holland, Italy, Germany, Yugoslavia or Australia, where they performed. However, KwieKulik’s art seemed to be doubly isolated, first due to the political isolation of Poland in the 1970s and ’80s, and secondly due to the specific, sociopolitical and cultural contexts of their art. Today, although the political isolation has been abolished, reception of KwieKulik’s art is still at best marginal. As a result, the comparison between the two couples raises the question of the location of the center and the margins in the current discourse of artistic geography. Artistic centers, situated mostly in the western world, favor art that makes use of universal idioms, while art defined by regional or local contexts is still considered marginal.

Katarzyna Michalak is an art critic especially interested in the problem of the interrelation of gallery space, art object and audience.