n. paradoxa vol. 4 1999.

Sarah Wilson

Discovering the Psyche Zofia Kulik

Time present and Time past

Are both, perhaps, contained in Time future

And Time future contained in time past.1 T. S. Eliot: ‘Burnt Norton’, 1935, from ‘Four Quartets’, The Complete Poems and Plays of T. S. Eliot, London, Faber and Faber, 1969, p. 171.

Hestia: Sermons of Fire and Stone

‘You must come to my house’. To understand Zofia Kulik and to understand this exhibition in Poznan with so many images and artefacts, one must understand the hour upon hour of work made in her home. Hestia, the veiled goddess of hearth and home, has been appointed as the presiding spirit of Both Home and a Museum, the strange monumental sculpture that stands in the first hall of this retrospective, partly encircled by the balustrade from the entrance to Kulik’s own house. Dislocated, then, in space, uncanny in its rich trappings, Both Home and a Museum is eloquent with a certain pathos, a sense of the obsolete that splits the twin meanings of ‘Mahnmal’. Specific commemoration is absent, leaving merely a sign of warning, anticipation. A figure from contemporary advertising, ephemeral, photographic, Hestia paradoxically challenges the concept of stone itself, as she walks among the classical columns- pre-catastrophic or post-catastrophic? We turn to her in crisis, in times of conflagration, yet the apotropaic goddess also insures against catastrophe to come. Like Tiresias of’ ‘The Fire Sermon’ in T. S Eliot’s The Waste Land, she has ‘foresuflered all’.1 Eliot, ‘The Fire Sermon’, The Waste Land, ibid., p. 69. A ‘materialist dialectic indeed. Is her mysterious body moving into stone or out of stone? Do we imagine the young woman becoming older, petrifying the past and its memories as her mission assumes monumental proportions? Or the older woman, moving from the controlled languages and patterns of a stony era – where violent and parodic protest, focussed on the body only, was nonetheless ephemeral – to a mature and powerful period of self-realisation?

Memory: The Question of Archives

‘I am an artist of the 1970s… For us 1981 started in 1974.’1 Unsourced quotations by Zofia Kulik are comments made to the author in Lomianki, November 21st – 23rd, 1998. Again and again it is emphasised: that to understand Kulik’s work one must understand those years, those passions and those memories.1 The homelessness of this performance archive is scandalous. Polish museums and art history institutions please note! Protest focused on the body. It was violent, parodic, ephemeral. Kulik has described the liberation of those years: the first collaborations from 1969-1971, the release from traditional art objects, into art as process, new media, as ‘the escape from defined forms, the practices of mechanical registration, self-administration, opposition to officiality, building a private base for independence.’1 Zofia’s words from a fax to the author of March 9th, 1999. Much laughter, good humour, good memories were generated in theatre and performance contexts whose roots go right back to the aftermath of the ‘Polish October’ of 1956, and the subsequent accommodation of postwar existentialism with Eastern regimes, giving rise to an ‘absurd’ so recognisable in the work of a Jann Kott or a Kantor. The internationalism of the later performance art years in Poland was particularly evident at the ninth Krakow meeting of 1981, where KwieKulik performances joined those of Mary Kelly, Stuart Brisley and a host of Polish contemporaries, including many strong female artists like Ewa Partum or Christine Chiffrun for example.1 Stuart Brisley alerted me to the important retrospective catalogue Spotkania Krakowskie IX, 1981, Cracow, BWA Contemporary Art Gallery, 1995. For women artists, see also Artystki polskie, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, 1991, (Wroclaw, Warsaw, Krakow) im Zaklad Narodowy Ossolinskich, 1991 and Voices of Freedom. Polish Women Artists and the avant-garde, Washington, National Museum of Womens’ Art, 1991. Experiencing these performances as documentation only, not their unfolding in real time, I see the photographs of the KwieKulik era as strangely disturbing. So often the heads are covered, disguised, interchangeable and we witness an abject and uncanny twinning; heads in buckets full of garbage (Activities for the head II, 1978); or clay stuck over the twinned heads, to be sculpted, monstrously, in performance (There and back from Activities for the Head, Krakow, 1981). The anti-repressive political thrust of these actions was clear, yet these performances seem to be lived experiences for Kulik of drowning and suffocation: ‘I was so silent, I could not speak. I needed someone (Kwiek) to be between me and my world.’1 Fax, March 9th, 1999. And this personal repression was part and parcel of the critique, passionate, yet still anti-subjective and idealistically Communist in its agendas: a belief in the ‘real’, a desire to to ‘test’ Communist Party dicta, the criticism of concrete facts, and reactions to ‘events, especially bad events.’

Zofia Kulik & Przemyslaw Kwiek Monument without Passport in Fine Art Salons (1978) performance, Sopot,1978

Martial law coincided with Kulik’s move from a cramped Warsaw flat to the Lomianki house where she would abandon the supporting structures of the performance years, rebelling against the group and the couple as her modus operandi. Yet similar motifs, similar gestures continue from the performances through to the photopieces, such as Kulik’s raised arm in Monument without Passport (1978) or insignia such as the Polish flag in The Semantic Monster (1984).1 In 1981, in Paris, the Centre Georges Pompidou, was emblazoned with ‘Solidarity’ banners. In ‘PresencesPolonaises’, I discovered Polish Unism and Witkiewicz; the ‘official’ nature of this show and omission of the performance and post-performance generation was unclear to me. Contemporary Art from Poland, Walter Philhps Gallery, Banff, 1986 gives a description in English of these actions in the contexts of Kwiekulik’s contemporaries. Curiously, it was the ephemera of these events, the archive of the PDDiU (Action, Documentation and Propagation Workshop), that would herald Kulik’s rebirth as an artist.

Portico of Zofia Kulik’s house, Lomianki, Poland, 1982

For behind the immense panoply of twentieth-century history displayed here in Kulik’s retrospective, and the working archive from which it is constituted, in her wonderful ‘house of memory’ with its apparent fullness: drawers of old postcards, thousands of labelled, photographic negatives, piles of textiles, Indian moulds, dried flowers, teazles, houseplant leaves, a crystal bowl, a sewing machine treadle, cogwheels, ‘Alice’s Adventures in Fucked Wonderland’ (a rayogram with dust and hair) – behind this working archive is another archive: that same huge and homeless archive of the performance art period. Its presence hovers as an invisible palimpsest behind the new images. To superimpose these two archives would superimpose the small narrative, ‘KwieKulik’, with the metanarrative of history displayed in Kulik’s epic works – or as T.S. Eliot would have it, the personal and the impersonal. Every individual is marked and made unique as history inscribes itself in our lives. We are generally the minor protagonists, the anonymous dancer in the chorus line, the munitions worker behind the conveyor belt, the soldier in the parade, a figure in the crowd. Some of us, however, become artists. Kulik declared: ‘In 1984 I started to speak’.

Geographies and Grammars of Ornament

From axes of time to the axes of space. In the international exhibition ‘Wanderlieder’, Kulik felt herself to be ‘a ‘quotation’ from the East’ involving all the problems of ‘double identity’ as she took her place among a constellation of Western artists.1 See Doppel Identitat. Polnische Kunstzu Beginnderneunziger Jahre, Wiesbaden, Landesmuseum, 1991, and Wanderlieder, Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, 1991-2. Coming from England to meet Zofia Kulik, I found my mental geographies changed, and with them my ideas of Poland’s positioning in time and space, my understanding of the lineage of Polish art and its possible futures.

‘Like every nation, we Poles like to see ourselves at the centre of the world, or at least of Europe, at the intersection of imaginary axes which connect the furthermost northern and southern, western and eastern points….To the Poles…the North is the cold waters of the Baltic, Scandinavian boats, castles of the Teutonic knights and the sacred oaks of Mickiewicz’s Lithuania. Our East is the Greek Byzantium, Slavonic Ruthenia and Tartar-Mongolian Asia, the coifs and coral beads of orthodox princesses given in marriage to rulers of Poland’s Piast dynasty. Ruthenian frescoes in the castle chapel of the Jagiellons, and those schismatic folk icons aginst which a losing battle was fought right up to the end of the sixteenth century by Post-Tridentian bishops. Our South is Turkish half-moons and horse-tail ensigns, Persian tents and carpets, coats of mail and robes, those knightly customs and splendours which the chroniclers of the gentry called “Sarmatic” – the term synonymous with ancient Polish qualities. Our West is the Latin of the Middle Ages, Renaissance Florence and Padua, Baroque Rome and the thrifty Netherlands, the French rationalism and Enlightenment – it is Paris, which in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “opened the eyes” of several consecutive generations of Polish painters—Apart from that obvious Latin influence, the great rational artistic systems of the West have remained strangers to our art…We were particularly drawn to, and fascinated by, all that our Latin tradition rejected. Orthodox Europe, inspired by Byzantium, and the Oriental works of Islam, not so much coloured our art with additional, rather exotic hues, but rather provoked us to confrontation.’1 MieczyslawPoresbski: ‘The Genealogy of Contemporary Polish Art’, Projekt, no 5-6,1969, in conjunction with exhibitions of Polish art at the Palais Galliera and the Petit Palais, Paris, Kulik collection.

Zofia Kulik, Strażnicy Iglicy (1990), 240 x 150 cm

It was Zofia who underlined this passage, Zofia who explained to me the exotic history of the ‘Polonaises’ in her culture: Oriental carpets from a different Poland, the Poland looking South, carpets whose patterns and ornaments structure Kulik’s photomurals.1 Kulik indicated Volkmar Gantzhorn: The Christian Oriental Carpet, Taschen Verlag, 1991, and the literature from Alois Riegl’s Altorientalische Teppiche, Leipzig, 1891 onwards with special reference to the reception in Poland (see Krakow, National Museum Collection Catalogues vol. III, Eastern Carpets), In October 1934, carpets were used as backdrops tor individual paintings at the Salonie Instytutu Krzewiena Stzuki (Artelier 1, 1993, p 53). Contemporary Afghan War rugs, woven with tanks and helicopters, make a poignant crossover with Kulik’s work – a voice from ‘theOther side’. The history of ornament is a history of conquest and the rise and fall of empires. At the height of the British Empire, Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament (1856) demonstrated the structures and motifs of a history extending from ‘The Ornament of Savage Tribes’ to ‘Italian Ornament’ within an implicitly Hegelian and Darwinist framework of evolution. There was no place here for the concept of genocide.1 Owen Jones: The Grammar of Ornament. London, Messrs. Day and Son, 1856; reprint Studio Editions, 1986. The conjunction ‘ornament and crime’ was made by the modernist Adolf Loos but he could not imagine the atrocities of our century. After Auschwitz, Andre Malraux, in Le Museé lmaginaire (1947) traced the passage of a smile from a Khmer Buddha to the cathedral of Rheims- as a passage ‘transcending’ millions of deaths. Kulik’s work also demonstrates the saga of the transmission of ornament, from the prehistoric zig-zag or the Turkish carnation to Polish national costume or the contemporary pattern on a tie or a frock.1 See Ubiory w Polsce (Costumes in Poland), Warsaw, Stowarzyszenie Historykow Sztuki, 1992, 1994. It is not only the rotational symmetry of the carpet but the terrifying conjunction of ornament and death which separates her work from Gilbert and George’s Worlds and Windows: jazzy, nostalgic, vertically-arranged postcard-poems to what was still Thatcher’s Britain in 1989.1 See Worlds and Windows by Gilbert and George, London, Antony d’Offay Gallery, New York, Robert Miller, 1989 (the postcard unit serves as individual tessera). Kim Levin in ‘Conceptual Carpet’, Village Voice, June 12th, 1990, contrasted Kulik’s ‘Idioms of the Socages’ at the Postmaster’s Gallery with Gilbert and George’s simultaneous Robert Miller show. Ornament and death? Kulik makes the conjunction again in the colourful and tragic Ethnic Wars series, where skulls on Paisley shawls rework a “Vanitas still life” for Kosovo. The exuberant cults of the Mexican Day of the Dead attempt to conjure grief with the same celebration of decoration. Zofia’s first sculpture, in fact, was the copy of an Aztec goddess, Coatlicue, her face a skull, her skirt a braided plaiting of live serpents.1 See Jerzy Truszkowski: ‘The structure of Kulik’, Magazyn Sztuki 10, 1996. Carving those complex patterned braids, she worked in stone as her mother had worked with needle and thread. Kulik labours with the patience of her ancestors.

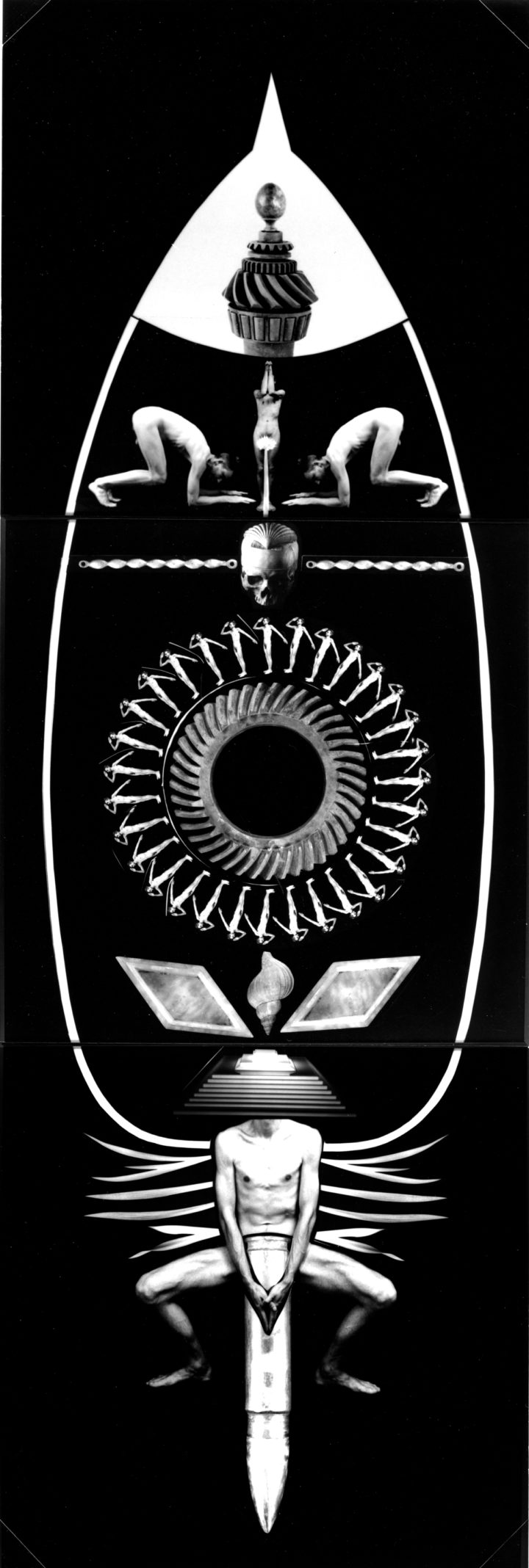

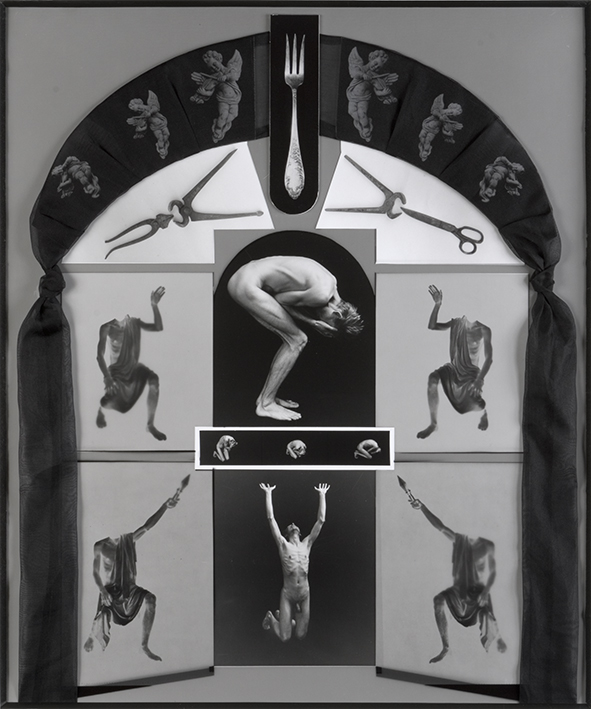

The Male Body

Kulik’s ‘grammar of ornament’ is based on the silhouette, the white on black silhouette of the photogram and the negative. The use of the human body as pattern goes back to the origins of time – to the zig-zags representing man himself that Kulik evokes in From Siberia to Cyberia, to the silhouettes on Greek vases. Roland Barthes, writing on the Art Deco figures of Erté, categorised the silhouette as this place (this form) intermediary between the fetish and the sign… a strange object, at once anatomical and semantic, the body, become explicitly drawing, very delimited from one point of view, totally empty from another… they are adorable (one can still desire them) and nonetheless, already entirely intelligible (they are signs of an admirable precision). As he speaks of Erie’s female ‘gynecographies’, so we could speak equally of Kulik’s ‘andrographies’, her writing with the male form, and likewise deploy Barthes’ musical analogy, comparing the silhouettes to Jean-Sebastian Bach who ‘exhausts’ a motif in all its inventions, canons, figures, ricercari and possible variations.’1 Roland Barthes:’Erte ou A la lettre’ in Erte, Milan, P.M. Ricci ed, 1973, in Roland Barthes: L ‘obvie et l’obtus. Essais Critiques III, Paris, Gallimard, 1982, pp. 102-3.

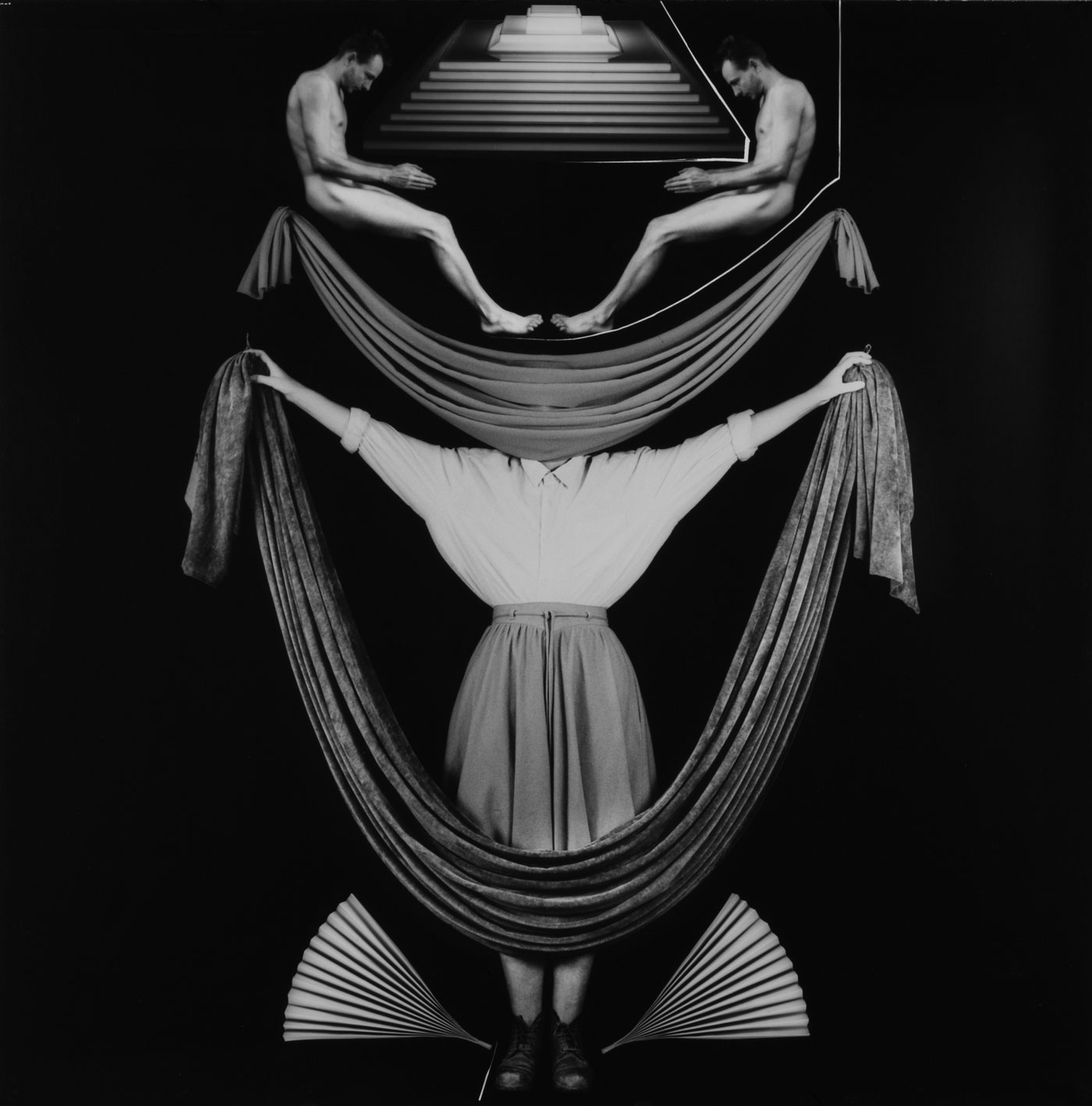

Kulik sees her model, Zbigniew Libera as a scientist, doing gesture after gesture. The grammar of ornament spells out messages here whose meanings are obscure. Yet there is evidently a certain delight, an element of the ‘caprlccio’ in this sporting with the male body; at will doubled, trebled, multipled, depersonalised, inverted and distorted into strange symmetries, monstrous chimera, destroyed even: a man is a splinter I can crumble at my own will.1 Zofia Kulik: statement of 1989 reproduced in Idiomy Socwiecza/Idioms of the Soc-Ages, Lomianki, 1990. The caprices of arrangement are exercised after the pleasures and surely the strains and frictions of the posing sessions: Libera naked under strong lights in a bare room; Libera as a tumbling figure from Memling; as a kneeling figure from William Blake; Libera, arm outstretched, rather pathetically parodying Aulus Metellus’ rhetorical gesture as it is adapted by G.D. Alexeyev’s sculpture of Lenin, The Commander Calling (1924); from toga to suit back to skin… Libera as swastika, as Catherine wheel, as fallen angel. Libera dragging an inordinate amount of drapery knotted in a huge bulge over the genitals, then niched in a crustacean’s tail; Libera holding swags of cloth aloft while the negative imprint of spearheads conjure a giant erection or, with his body multiplied into a circle around the great patriotic, socialist-realist sculpture from Magnitogorsk, making a series of cogs in a wheel, pleats of ribbon around an old, discarded medal.

Yet there is also Libera as a young man with a beautiful and poignant body, slim and vulnerable, his delicate musculature revealed by a tender play of shadows. Libera’s patience is surely tried, yet he is loved, immortalised, monumentalised as the obsessional protagonist of Kulik’s epic pieces. And, of course, Kulik’s obsessive repetition indicates an absence, the absence of one who is lost and is not Libera: fetish, sign, motif, loved one, lost one, Other, yet also a character in search of his author.

Double Identities

Libera as a character speaks for ‘his’ author. The creator must put herself imaginatively in the place of the protagonist. As a woman, Kulik confronts a paradox first, perhaps, made explicit in Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, of the difficulties of empathising with and objectively constructing male personae, in orchestrated scenarios that evoke a desperate, cruel and often grey history.1 See Virginia Woolf: Orlando, London, Hogarth Press, 1928. For the modern woman whom Zofia Kulik has become, how complex it must be to attempt to imagine this sexual difference at a personal level; to attempt to imagine the psychic and perceptual differences of the world between the sexes. Feeling as she must with the women whose lovers, husbands, fathers were sent on missions to fight, to kill, to torture or be tortured, the familiar is ‘unheimlich’, horrific even. Kulik must imagine enactment at the level of the naked body beneath the militarised army element. Klaus Theweleit’s deconstruction of the mentally ‘armour-plated’, nazified body, programmed to despise women, yet to fight for a fantasmatic amd idealised ‘Motherland’ has now moved from the explosive and divided context of 1970s Germany to become a given of contemporary analyses of the white male psyche.1 Klaus Theweleit: Male Fantasies vol 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History 1977 Minneapolis, University of Minnetosa Press and Oxford, Basil Blackwell 1987; vol 2: Male Bodies. Psyclioanalysing the White Terror 1978, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota and Oxford, Polity Press, 1989 Beneath each robotic, uniformed soldier, each arm carrying gun or carrying banner – is a naked man, a mother’s son.

Zofia Kulik From the series Gates (Black Julie) (1987-89) 60 x 50 cm, photo collage

Zofia has described those different male and female universes, perceived at home as a child; her mother’s domestic space in the apartment within a military barracks, looking out to the parade ground where her father organised and participated in countless military excercises. Her mother, the homemaker, the dressmaker, lived in the ‘soft’ world of carpets, kelims, textiles, embroideries and printed cottons, fashion talk, gossip and visits from elegant clients, where even the premium on economy – in creating a meal, in cutting out a dress pattern – became an occasion for marvellous and skillful artistry.

In the form of my mother I put the content of my father. The kelim-like photo-fragments in Kulik’s work dazzle and disturb; the images have the crystalline fragility of a moment held in a kaleidoscope image. In English the very word ‘dazzle: to confound with brilliancy, beauty, cleverness’ has its military dimensions of deception and camouflage: the ‘dazzle-painting’ on the sides of ships: the dazzle which conceals identity and numer.1 Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, London, 1973, p, 330. The psychoanalytic dimension of this unresolved struggle between masculine and feminine, creation and destruction, exposure and hidden identity, accounts for the feelings of both violence and impotence that Kulik has expressed. The body as sign and ensign exists in dazzling tension in the hard/soft light/dark patternings of the splintering photographic surface.

Fallen Angels: Manichean Light

Necessarily, just as Libera’s body first and foremost evokes the body of Christ, Kulik’s work with its darkly Gothic evocations, and arching, pointed structures is framed by the spiritual, the eschatological. The cry of the unbeliever is the cry of Christ Himself: Lama sabacthani? I Why hast Thou forsaken me? Even within the post-Solidarity Church, the constraints of rhetoric, of political as well as religious discourse, apparently continue. The systems of ordering, of hierarchy, of discipline and punishment, of control over minds, over bodies (of women, especially) together with the demand for self-sacrifice and self-repression, equivalent to those of the military, distinguish the Church as institution from any longing for God or cry of the soul. How to be post-Communist and not to be Catholic?

But in front of whom is one to be

humiliated nowadays?

There is no god, no leader, no mystery.

So whom is one to serve?

That’s it.

I am afraid of myself – I am scared that

I can feel subordination so perfectly and can visualise it.1 Zofia Kullik, 1989, in Idiomy Socwiecza / Images of the Soc-Ages, op. cit.

Zofia Kulik The Guardians of the Spire (1990), 240 x 150 cm, Private collection, London

The promise of religion itself, of a religious Paradise is lost; yet the Manichaean power of the dialectic betwen good and evil, light and dark, redemption and damnation, continually haunts Kulik’s work, whose very basis, from a technical point of view depends upon light itself, upon illumination and its withdrawal, on the ‘positive’ and the ‘negative’. (It was a priest who first showed the young Kulik projected images – slides and the ‘miracle’ of the epidiascope). Why black and white? I’m a sculptor, Kulik sees the world in relief and shadow. Her ground is darkness. We recall John Milton’s apocalyptic vision of hell, his Pandaemonium: No light, but darkness visible. Against this manifesting of visible darkness in Kulik’s photopieces, dance the stars, crowns, rays of light, the haloes and flaming hearts, shining hosts. And as counterpoints to this light, dissolved through photography into the same ghostly images, are the solid points : penetrating weapons, spiky monstrances, gravestone chains, thistles, flagpole tops, phallic shell-cases combined with idioms of the Church and idioms of the Socialist ages. One recalls Andrej Wadja’s Ashes and Diamonds of 1958. Along with the whitened and multiplied bodies of Libera or the anonymous soldier, dancer, swimmer, these insignia pattern Kulik’s surfaces, retaining and losing their meanings simultaneously within the greater design.

Zofia Kulik Wszystkie pociski są jednym pociskiem / All the Missiles are One Missile (1993), 300 x 850 cm. photo collage

All the Missiles are One Missile (1993)

The impact of quantity, of number in Kulik’s work is reiterated in screen after screen, pattern after pattern, the ‘quantity which builds aesthetics’. Yet quantity is also an alibi. A spatial synchronicity destroys all private space as it destroys narrative, causality, the blunders of history, the logic of its unspeakable crimes. The new technologies exhibit no moralities or hierarchies of classification. Yesterday’s news which was live is now dead and like its protagonists is now digitalised. Spatiality is numbed by this accumulation of evidence.

In the photomontages of the modernists, Rodchenko, El Lissitsky, and particularly Gustav Klucis with his duplicated, miniscule Lenins in Moladaja Gvardia (1924), the repetition of heads in a crowd, of gymnasts, strikers, soldiers, bayonets glorified impersonality. The oblique shot captured a fragment which stood for the masses as a whole, the entire Soviet collective. Numbers under socialism were therefore celebratory, a sign of the ‘will to power’. Yet Kulik’s kaleidscope principle turns number into madness; her obsessive use of bilateral and rotational symmetries dissipate all linear rationality. This reference to insanity becomes explicit in figures such as the headless draped female on the catalogue cover of All the missiles… whose face is disturbingly revealed on the back cover. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, (1972) is inverted; we confront a ‘Totalitarianism and Schizophrenia’, in which dissolved, pixellated, repetitious women’s crotches, camera in water, shot from underneath, become a counterpoint texture to stronger foci, and the maniacal, seemingly arbitrary miniaturisation of men blown-up into motifs. The all-Seeing eye of Christian humanist perspective has abandoned the scene; mad implosions and explosions negate any remaining remnants of a ‘logic of history’ or ‘truth of images’.

All the missiles are one missile=All the women are one woman, Kulik created this title for her epic work as a tragic/ ironic inversion of T.S. Eliot’s phrase relating to female voices within the polyphonic structure of The Waste Land.1 ‘Just as the one-eyed merchant, seller of currants, melts into the Phoenician Sailor, and the latter is not wholly distinct from Ferdinand Prince of Naples, so all the women are one wonman, and the two sexes meet in Tiresias. What Tiresias sees, in fact, is the substance of the poem.’ Notes to part III “The Fire Sermon’, The Complete Poems and Plays of T.S. Eliot, op. cit., p. 78. Eliot, the modernist, espouses the persona of the seer, Tiresias, who speaks out of time and beyond sexual difference to depict a historical fresco of fragments, fragments redeemed from landscape of desolation: these fragments I have shored against my ruins.1 Ibid., p. 75. See T. S. Eliot: Poezje Wybrane, Warsaw, Instytut Wydawniczy Pax, 1960, and 1988. Kulik’s post-modern consciousness is riven with question of double identity. She is haunted yet revulsed at the complicity of modernism with a dehumanised figure as war machine but espouses the same apparent impersonality. Like Eliot, whose ‘Notes’, combined willed preciosity with the imperative to source the voices of his poetic text, Kulik has provided the necessary gloss to All the missiles are one missile, in her ‘Notes’, published in 1997 to accompany the work as it was displayed in the Polish Pavilion the XLII Venice Biennale.1 An Iconographic Guide to All the Missiles are One Missile, Warsaw, The Zacheta Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1997.

How does individuality function behind the fresco? This is not a cold but an intensely emotional work; Eliot’s concept of the ‘objective correlative’, elaborated through a consideration of the most complex personal problems – those of Hamlet – may provide a key: The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an ‘objective correlative’; in other words a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula for that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experiences are given, the emotion is immediately evoked.1 T.S. Eliot: ‘Hamlet and his problems’, The Sacred Wood, London, Faber and Faber, 1920. And Eliot again, in his celebrated essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, insisted upon the heritage of the whole of European literature, which, ‘speaking through’ the poet, is the source of his individual voice.1 T. S. Eliot ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, ibid. op. cit. His was an extraordiarily non-Marxist vision of the transmission of meaning and style diachronically through history, in direct opposition to the essentially synchronic vision of art’s superstructural ‘production’.1 Let us not forget Eliot’s Anglo-Catholic position at this moment, a moment of religious revivalism where his interest was divided equally between the seventeenth-century sermons of a Bishop Andrewes and the voices of English metaphysical poetry, a Polish audience). Here, Eliot surely anticipated texts such as Roland Barthes ‘Death of the Author’, 1961, and the philosophies of deconstruction that now govern concepts of personal identity, shot through, ineluctably, with the discourses of time present and time past.

Yet, from Eliot to Barthes, these great male voices in the arena of literary and philosophical production ratified an unchallenged hierarchy of ‘those who are allowed to act or to speak’ for society. As we attempt to read All the missiles are one missile, and traverse Kulik’s magnetised visual spaces, we are aware, beyond questions of formal and political content, of her voice, of her choice, of her laborious making, developing, putting together; of her ascetic and self-imposed isolation required for the carrying out of this epic task; and finally of her resolutely democratic insistence, as an informed invidual, of the right to make this choice and to speak out for – and against – her century.

Zofia Kulik. Detail of The Column (Monstrance) (1995), 150 x 50 cm. photo collage

Why Eliot? Language, too, has played its role in Kulik’s creative process. Just as Czeslaw Milosz analysed language’s function within the grey universe of Eastern doublethink, in Zniewolony umysł (The Captive Mind), 1953, so Kulik has reflected upon the destruction of the Polish language under Stalinism, dramatic and painful after the war, the brutal excisions and simplifications, a surrounding fog which also you have in you. The Soviet eradication of the introspective, post-Romantic, post-Freudian subjectivity that was all Europe’s heritage before 1939 was one of Eastern block’s greatest tragedies: The psyche under Communism didn’t exist…. We were prepared to be scientists. Personal motivation, or the driving force of a private relationship, were inadmissible in terms of a Communist epistemology which transmuted desire into abstract nouns: Slawa, Milosc, Nadzieja. Eliot revealed to her the voices of that lost subjectivity, catching her mind’s eye and her ear. Eliot became a means of thinking new thoughts, of becoming a new subject. I was not taught to articulate…. Sometimes I need to find myself between words.1 Kulik sent me a text comparing cognate structures in Polish and Indo-European languages including English: ‘siostra – sister, wdowa – widow’: An Outline History of Polish Culture, Warsaw, Interpress Publishers, 1983, p. 41. Kulik has a softer and more tentative voice in English. Yet, like Eliot, Kulik is still reticent: I give myself no permission to expose private things.

Ethnic Wars: Compassion Fatigue

Blue skies, hot sunshine, blue ‘peacekeepers’ uniforms, a tanned young boy: Luc Delahaye’s photograph of United Nations soldiers and refugees, taken at Tuzla in July, 1995. The boy’s arms cross his chest in a futile gesture of self-protection and supplication as he cries; his relatives weep-anonymous women wearing bright. Paisley scarves – all the women become one woman. They are distraught at the loss of men and home. In the global era of the celebrated ‘World Press Photo” (such was Delahaye’s honour) perhaps only Kulik’s device of metonymy, the sharp and disturbing juxtaposition of brilliant shawl and skull, a memento mori for our times, can jolt us out of ‘compassion fatigue’. This new term, describing the self-protective device of the citizen as telespectateur, TV watcher, has a price tag. She – or he -is bombarded with daily atrocities; feelings fluctuate between rage, impotence and a numbing anaesthesia. The ‘compassion fatigue’ factor is as crucial to calculate for the TV news producer as for the managers of relief operations or of charities. Grotesque, yes. Kulik’s Ethnic Wars, trigger an uncomfortable self-knowledge in each TV watcher who is involved, by proxy and at a distance, in this modern dance macabre. The serial display of cibachromes represent as repetition the individual torture or killing of separate, anonymous victims. From time to time a moment of strangeness or pathos is registered within the televisual flux as a kind of Barthesian ‘punctum’. Kulik shows me a television clip: African Masai warriors interviewed in their native costumes and on their native soil after fighting in Bosnia. Incredulous at the slaughter by white soldiers of women and children, they protest: Bless the women. They are the backbone of our society.

Burning burning burning burning

O Lord Thou pluckest me out

O Lord Thou pluckest

burning 1 T. S. Eliot: ‘The Fire Sermon’ (conclusion), op. cit., p 70, significantly what Eliot calls the ‘collocation’ of the Buddha’s Fire Sermon and Saint Augustine’s Confessions, ‘two representatives of eastern and western asceticism’, a culminating moment of The Waste Land (Notes, p.79).

From Siberia to Cyberia

The challenge of representation becomes ever vaster. From Kulik’s diploma piece at art school: five hundred slides, very many of a naked woman in academic poses, taken over a year (a home-made Muybridge), to the Studio of Activities, Documentation and Propagation (PDDiU)of the performance years with its archival remit. Kulik’s project of self-realisation in photographic and sculptural work then expands, filling larger and larger spaces: from the major piece, Favourite Balance, 1990, for Wanderlieder in Amsterdam to All the missiles… in 1997; from the seventy-five panel mounted photoarchive displayed for the first time in this show, we confront, at last, From Siberia to Cyberia, her final twentieth-century epic. As Poland joins NATO in March, 1999, the Polish president, Aleksander Kwasniewski, announced that now the final end of the second World War hand been reached and the division of Europe overcome. In London the debate is not this but the concept of ‘the long nineteenth century’, structured by the capitalism / socialism debate, which came to a close in 1989. What, then, was the twentieth century?

In her dark room Kulik organises trays of negatives, the Ilford photographic paper defining the size of the each element, like tesserae in a huge mosaic. Piles of newspaper and her broadcasting diary are stacked near the television; she can now speed up her work with a video. Electronic culture yes, but from my private, ordinary position. To miss not a moment to work like a hunter – this is why Kulik has to work at home, where high technology meets craft practice.

Kulik has shown me the history of Poland’s three uprisings in lithographs by Artura Grottger from an old book belonging to her father, and the depiction of groups on their way to Siberia by Wyspianski Malcevski; she told me of the poetry of Adam Mickiewicz. Siberia itself is an old theme in Polish art. Relatives of her family were sent by the Soviets to Siberia; she explained how Polish ‘enemies’ were co-opted for a Polish army in the USSR after 1942. The name of Siberia evokes camps, slave labour, incarceration, the long histories of a barbarous Other. Cyberia, the pun, already spawns a thousand websites. Websites in a cyberspace which Kulik cannot access from her darkroom at home where she weaves together her Siberian fresco like a Penelope. Yet Kulik’s pixellated surface of grey TV images serves as both warp and weft, as grid rather than content, the support of a meaning becoming ever more ghostly, the simulacrum of a simulacrum. Here, the heroic tradition joins the stitch: the zig-zag signs of prehistoric man, abstracted points of ‘heads’ and ‘phalli” stitch together her surfaces, visually linking up with the crochet pattern books, the Robotki reczne of a thousand Polish hearths.1 See Carl Schuster and Edmund Carpenter: Patterns that Connect. Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art, New York, Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1996 (in Kulik’s library). The positive or negative electronic impulse equals the stitch; to keep or lose eyes (to ‘drop stitches’ in Polish) so often equates with losing lives, losing souls. The East/West story is one of delayed reception; the transmission of ornament also. Working in Britain or America, Kulik would be working with electronic media; From Siberia to Cyberia would be displayed on a video screen or at least with back-lit photo-boxes. Poland’s own cyber-elite, its newest generation, exists, let us remember, equally so near and yet so far, further and further from the obsessive need to recall the Socialist ages.

The disasters which mark this end of millennial, are also the archives of evil (les archives du mat) writes Jacques Derrida in Mal d’Archive.1 Jacques Derrida:‘Priere d’inserer’, Mal d’archive, Une impression freudienne, Paris, Gallimard, 1995 (developed from a lecture at the Courtauld Insitute of Art, June 5th, 1994 at the symposium: ‘Memory. The Question of Archives.‘ The Mal Archive Fever. A Freudian Impression (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1996) conveys both enthusiasm and illness. Beyond the screens of the pixellated world which freezes the atrocities and paraphernalia of our century and its ‘burning evidence’ lies the patterning, the care, the colour; the roses of Ispahan and the carnations of Turkey, the warmth of woven textile and and knotted carpet, the deep rhythms of the patterns which persist. Derrida reminds us that ‘archive’ derives from ‘arkheion’ (a house, in Greek), that archives take place within a context of domiciliation, that ‘the pain of the archive’ is the necessary double of ‘archive fever’.1 Jacques Derrida: Mal d’Archive, op.cit., p. 12. A plaster cast of Michaelangelo’s Moses, the paradigm for Freud’s studies of monotheism, and for Derrida’s study of the relationship between ark, archive and covenant, was attacked by Kulik at art school, and clad in a patchwork harlequinade… It is thanks to Kulik’s domiciliation, her house of memory under Hestia’s aegis, that we may now survey her archives of the century. Out of the pain and the madness of that archive she posits not only a grand design but the mandelas of healing and of our archtypal memory: I am organiser of the plenitude which attacks me. The organisation of a century into pattern, or a leaf of frost on a window in Lomianki: detail spiralling into detail contains the lesson of the fractal – and its own beauty To spiral into the centre of the body is to encounter the individual as microcosm, to discover a psyche more complex than any Cyberia, what Kulik has daringly called The Splendour of Myself.

What, you ask, was the beginning of it all?

and it is this…

Existence that multiplied itself

For sheer delight of being

And plunged itself

into numberless

millions of forms

So that it might

Find

itself

Innumerably1 Sri Aurobindo, quoted in Arthur C. Clark’s narrative for a Lemoir and Gordon Film on fractals, 1995 – seen with Zofia, November 23rd, 1998.

Sarah Wilson, London, March, 1999.

This text was completed a few days before the tragic renewal of genocidal policies in Kosovo and the NATO bombing of Serbia and Kosovo. A major retrospective exhibition of Zofia Kuliks’ work opened in Posnan, Poland in May 1999. Sarah Wilson’s essay was translated and published first in Polish to accompany the exhibition.